The minstrel boy to the war is gone,

In the ranks of death you’ll find him.[1]

In the mid-1850s, the Foundling Hospital began to send its boy musicians into the regimental bands of the British military. That decade saw the first, seemingly uncertain steps in a process which accelerated during the following years and in the end transformed the career prospects of the Foundling’s boys. This study will examine the early days, up to 1859, of the relationship between the Foundling Hospital and the military, when John Brownlow, the Secretary, developed the policy of sending boys into both the British Army and the Royal Navy. Sadly, for a few boys, this also meant entering ‘the ranks of death’.

Child soldiers have been used by armies since Ancient times and, more recently, they have frequently featured as members of military bands. Under Henry VIII, for example, ‘boy soldiers more often than men served as drummers, buglers and fifers’, the army that Charles I sent to Cadiz in 1625 contained the ‘usual complement of boy soldiers, for there was a continuing need for drummers, trumpeters and fifers’, and the eighteenth century, from Marlborough to Napoleon, saw a considerable increase in the recruitment of boys, including boy musicians.[2] In Dublin and London, respectively, the Royal Hibernian Military School (1770) and the Royal Military Asylum (1803, later renamed the Duke of York’s Royal Military School), both set up to educate military orphans, sent many of their boys into the British Army.[3] The Foundling Hospital had no such tradition, only very occasionally sending boys to the military. John Brownlow’s analysis of the destinations of Foundling boys between 1841 and 1847 showed that out of 79 leavers only one went to the Army and one went to the Royal Navy.[4]

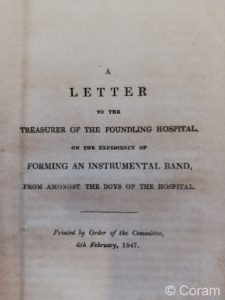

It was Brownlow, at this time the Treasurer’s Clerk (he would become Secretary in October 1849), who prompted the formation of a boys’ band at the Foundling Hospital, setting out the case in a letter to the General Committee on 5 February 1847. His arguments focused mainly on the internal discipline of the Hospital (the ‘moral’ effect), although he did have an eye to how it might benefit the boys in later life (‘their future welfare on quitting its walls’). In the questionnaires sent to five other children’s homes with boys’ bands, only one of his eleven questions asked if musical knowledge and ability ‘tend to their worldly advantage when they leave’.[5] Two institutions pointed to the way in which military careers had followed – the Royal Naval School at Greenwich briefly touching on how band membership helped boys to gain ‘good situations… In most cases the band-boys have gone to our Men-of-War’ and done well, and the Royal Military Asylum at Chelsea explaining that, ‘From the boys of this Asylum being generally destined for the army, those boys instructed in music here are received into Regimental Bands, by which they receive additional pay and advantages, and, from reports received, are generally found to have conducted themselves in a manner superior to the others.’ The Caledonian Asylum, where the band had only just been started (in 1846), anticipated the same: ‘much interest has been excited in the army in consequence of the establishment of our band, and applications have been made for boys to join the bands of different regiments…’[6]

It was Brownlow, at this time the Treasurer’s Clerk (he would become Secretary in October 1849), who prompted the formation of a boys’ band at the Foundling Hospital, setting out the case in a letter to the General Committee on 5 February 1847. His arguments focused mainly on the internal discipline of the Hospital (the ‘moral’ effect), although he did have an eye to how it might benefit the boys in later life (‘their future welfare on quitting its walls’). In the questionnaires sent to five other children’s homes with boys’ bands, only one of his eleven questions asked if musical knowledge and ability ‘tend to their worldly advantage when they leave’.[5] Two institutions pointed to the way in which military careers had followed – the Royal Naval School at Greenwich briefly touching on how band membership helped boys to gain ‘good situations… In most cases the band-boys have gone to our Men-of-War’ and done well, and the Royal Military Asylum at Chelsea explaining that, ‘From the boys of this Asylum being generally destined for the army, those boys instructed in music here are received into Regimental Bands, by which they receive additional pay and advantages, and, from reports received, are generally found to have conducted themselves in a manner superior to the others.’ The Caledonian Asylum, where the band had only just been started (in 1846), anticipated the same: ‘much interest has been excited in the army in consequence of the establishment of our band, and applications have been made for boys to join the bands of different regiments…’[6]

Brownlow concluded that the bands had had ‘a softening influence upon the temper and conduct of the children, besides opening to them additional means of mental recreation, and of profitable employment in afterlife’ – but he was far from seeing this primarily in terms of military careers, opining that musicianship would give the boys ‘a double means of living. We are becoming (if we are not so already) a musical people, and it is a fact that instrumental performers, engaged at concerts and elsewhere, are all (the principals excepted) filling other occupations during the day.’[7] The Hospital’s leaders knew of the likelihood that some boys would go on to enter regimental bands, but it was by no means the purpose behind forming the band and they had no sense that they were initiating a process by which the Hospital became a feeder institution of the British Army.

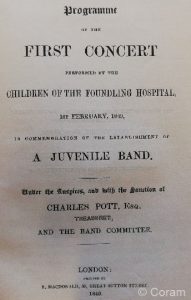

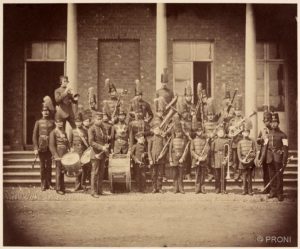

The band was duly established in 1847. Ten months into its existence, the Bandmaster of the Coldstream Guards, Charles Godfrey, called in to assess the band’s progress, deemed it still ‘inharmonious’ and ‘unsatisfactory’ (‘the Music is either badly arranged or incorrectly played… The mere circumstance of the tender age of the Boys is not a sufficient explanation of so imperfect a performance’, with ‘the Brass Instruments certainly play’d the worst’).[8] The Music Master was dismissed and replaced by James Twiddy. Under Twiddy’s leadership, the band performed its first public concert on 1 February 1849, not quite the anniversary of the famous Handel concert at the Foundling Hospital (27 May 1749), but the band and choir did include the Chorus from Handel’s Messiah.[9] The band consisted of up to 30 boys, though Twiddy estimated in 1853 that the ‘average number’ was only 24, aged nine to fourteen; they were ‘selected from amongst those who possess a musical ear…’[10] Towards the end of 1852, Godfrey of the Coldstreams was ‘taken by surprise’ by the rapidity of the band’s progress and put it down to the fact that Twiddy was ‘not only a good Instructor but a good Musician’:

The band was duly established in 1847. Ten months into its existence, the Bandmaster of the Coldstream Guards, Charles Godfrey, called in to assess the band’s progress, deemed it still ‘inharmonious’ and ‘unsatisfactory’ (‘the Music is either badly arranged or incorrectly played… The mere circumstance of the tender age of the Boys is not a sufficient explanation of so imperfect a performance’, with ‘the Brass Instruments certainly play’d the worst’).[8] The Music Master was dismissed and replaced by James Twiddy. Under Twiddy’s leadership, the band performed its first public concert on 1 February 1849, not quite the anniversary of the famous Handel concert at the Foundling Hospital (27 May 1749), but the band and choir did include the Chorus from Handel’s Messiah.[9] The band consisted of up to 30 boys, though Twiddy estimated in 1853 that the ‘average number’ was only 24, aged nine to fourteen; they were ‘selected from amongst those who possess a musical ear…’[10] Towards the end of 1852, Godfrey of the Coldstreams was ‘taken by surprise’ by the rapidity of the band’s progress and put it down to the fact that Twiddy was ‘not only a good Instructor but a good Musician’:

Nothing can exceed the improvement… I did not really expect to find them in such a state of efficiancy [sic]. I do not know any Institution of the kind where the improvement has been so great… I was altogether as much pleased with my visit the other day to the Foundling as on any occasion of the kind I remember… [T]he Boys generally appear intelligent and Healthy and I am convinced by long experience that playing Wind Instruments is more likely to improve than hurt their constitution… The Coldstream Band usually number about Thirty five, we have had but one Death for more than Ten years, and it is a fact that there is less sickness in the Band than any part of the regiment… Mr. Tweedy [sic] deserves the greatest credit for his exertions…

Godfrey’s correspondent, a frequent visitor to the Hospital to hear the band, ‘consider[ed] their performance quite unexampled for Boys, and I scruple not to say that it is better than that of some adult Bands in the army’.[11] Godfrey, once a boy drummer himself, having enlisted during the Napoleonic War, was destined to develop a close relationship with the Hospital and to recruit a number of its musicians.[12]

The first Foundling band boys to enter the military, Samuel Edwards (1851) and Richard Hopkins (1852), went to the Royal Navy, of which more is said below. The first reference to Army careers for the band boys appeared in the minutes of the General Committee in July 1853, when it was noted that two members of the Juvenile Band, Charles Jackson and Daniel Sharp, were ‘desirous of enlisting in the Army’ and that the Bandmaster of the 17th Lancers wished to recruit them. Twiddy reported that Jackson had been ‘approved by the Regimental Doctor’ but Sharp was ‘not fully approved’.[13] Two weeks later, however, it was reported that the Bandmaster of the 38th Regiment of Foot at Chatham wanted to take Sharp, Augustus Browne and John Rabnett. They were called before the Committee to be asked if they were willing, all three assented, and they were ‘permitted to enlist accordingly’.[14]

Augustus Browne

Augustus Browne (a member of the original band, he played trombone in the concert in 1849) had initially (March 1852) been apprenticed to a furrier, but he was re-admitted to the Hospital after three months when his master reported ‘that the boy was industrious and otherwise well conducted but had not sufficient capacity to acquire a knowledge of his business of a Furrier… Every thing he does he spoils and that I cannot let him do, in fact the boy never will earn his living at fur, for he cannot learn it.’[15] This was an inauspicious beginning for someone who was to emerge as a person of considerable merit. A year later, it was decided that he should be ‘placed on trial’ with a leather merchant, ‘with a view to an Apprenticeship’, but within weeks he was ‘permitted to enlist in the Army’ and the Hospital’s Apprenticeship Register had him volunteering ‘into the Band of Her Majesty’s 38th Regiment of Foot’ on 27 August 1853.[16] He was a particularly strong musician; in November, Twiddy noted that Browne played 1st Trombone and Sharp 1st Clarinet and commented, ‘Of 25 men & boys comprising the Band the above boys being the best players of the whole number.’[17]

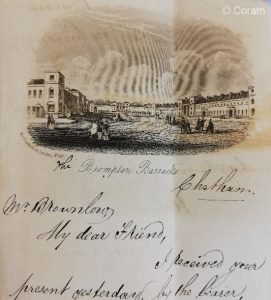

A few months after enlisting, Browne initiated a revealing correspondence with Brownlow and other individuals at the Hospital. In his first letter, sent from the barracks at Chatham on 30 December 1853, he referred to a physical problem about which we know nothing: ‘My infirmity is quite well and I am happy to say it has not troubled me for a long time, and I hope and trust it never will… My Two Comrades are going on well.’ On 12 January, he wrote that ‘Sharp & Rabnett are doing well. Rabnett wishes very much for a Bible that the Governors distribute to them upon being Apprenticed, Sharp has left his behind, but I have brought mine with me… We go to School every day and thereby keep up on Education.’[18] Subsequently, writing to Miss Soley, the Girls’ School Principal, he expanded on the latter point:

A few months after enlisting, Browne initiated a revealing correspondence with Brownlow and other individuals at the Hospital. In his first letter, sent from the barracks at Chatham on 30 December 1853, he referred to a physical problem about which we know nothing: ‘My infirmity is quite well and I am happy to say it has not troubled me for a long time, and I hope and trust it never will… My Two Comrades are going on well.’ On 12 January, he wrote that ‘Sharp & Rabnett are doing well. Rabnett wishes very much for a Bible that the Governors distribute to them upon being Apprenticed, Sharp has left his behind, but I have brought mine with me… We go to School every day and thereby keep up on Education.’[18] Subsequently, writing to Miss Soley, the Girls’ School Principal, he expanded on the latter point:

I go to the Regimental School every afternoon to keep up my Education as much as possible. Believe me ma’am, I have seen a great many Soldiers who cannot spell or write their own name, therefore I value a great deal more the Education I received at the Foundling, & I wish I could impress upon the Boys & Girls to learn as much as they possibly can, and pay attention to their studies, when they would some day reap the advantage of “Time” so devoted. I hope sincerely that my Sister will endeavour to correct her faults, according to her promise. I am getting on well, and like playing the Band very much…

I hope by my good conduct & maintaining good character, both now & ever afterwards, to prove myself worthy of the kindness of my Benefactors. When I’m on a foreign station, I shall not fail to communicate with you… My comrades Rabnett & Sharp are doing well, & I am happy to state that we live on friendly terms together as brothers.[19]

I still go to School to improve myself in every way, and I know the real value of Education. It is said by some that should any Vacancy occur in the Regimental Office, that if I take care of myself I shall be sure to obtain some Situation there…[20]

In February, Browne wrote to his ten-year-old ‘sister’ at the Hospital, Sarah Moore, who ‘was brought up by the same nurse as me, & therefore I am fond of her, as my real sister’. This letter is full of brotherly tenderness and advice reflecting the moral standards that Browne had imbibed at the Hospital: ‘Be a good girl… Maintain a good character, so as to be recommended in case of any rewards being given by any of the Governors, for, if you behave properly while you are young, you will do so during your lifetime.’[21] Browne also gave brief glimpses of his bandsman’s life: ‘We march out five miles distant, and the same back, playing [in] the Band, once a week, in order to get used to the Cold.’ When five companies of the regiment departed for Deptford, ‘We played the Band in front of them, leading to the Railway Station, at ½ past five this morning, which is the case where soldiers are moving from one place to another.’[22]

Browne took ‘the greatest pleasure’ in announcing that he was to travel much farther afield:

Our Regiment are preparing to proceed very shortly to Constantinople. We believe some time this month. I shall go with them, but it is said that I shall not be engaged in the War as I have not commenced my Service, in fact it will be a year more before I do so.[23]

Britain was about to go to war in Europe for the first time in four decades. The Crimean War, as it came to be known, broke out on the Danube in October 1853, when the Ottomans fought the Russians. Britain and France declared war on Russia on 28 March 1854, and the 38th Regiment of Foot was despatched to the area in April. At the beginning of April, Browne gave notice to Miss Soley:

I beg leave to acquaint you that our Regiment have received orders to be in readiness, and that a part of them are going very shortly and the remaining with the Band will shortly follow them…

Rabnett & Sharp are doing remarkably well, and I am certain it will be pleasing to hear they are more friendly with me than any one in the Regiment.

Should I return from the War, I hope I shall hear from you an excellent character of my young sister…

I do not know what moment the Regiment may have orders to advance. I have seen Diplock & Dalton in the 18th Regt. and they appear very comfortable.[24]

Similarly, Browne sent Brownlow a fond farewell:

I am happy to say that Rabnett & Sharp are still doing remarkably well and keep on strong friendly terms together, which I hope they will continue the same during my absence from England. I received your farewell letter a short time back, and feel grateful to you for heartily wishing me every success – and do not be doubtful as to my writing to you while in Russia, for what I promise I will perform… I suppose my next letter, if sent from any of the Turkish Dominions, will be very pleasing as I daresay I shall have much to communicate…[25]

It was in another letter to Miss Soley that Browne came closest to facing the prospect of death on the battlefield:

I will by all means write to you on the Eve of my departure to Turkey, according to my promise, and be sure, ma’am, that I will send you word when I arrive in that foreign country, to which I am about to proceed very shortly. I don’t suppose that I shall be able to come and see you any more before I go – perhaps we will never meet again in this world, but may we meet in heaven. I am not afraid to meet death in the field of battle, as such sudden death would seem to me as sudden glory – as I have not put off repentance till a dying day, because I have been taught that now is the accepted time, now is the day of salvation…[26]

Browne, but not Sharp or Rabnett (both still 15, making them 18 and 21 months younger, respectively, than Browne, who turned 17 on 21 March 1854), was sent out, and Sharp, with no sense of the glory of war, was full of apprehension (and prescience) about the danger his friend would face:

The Regiment went away on Tuesday last on board the Melbourne man of war vessel. Browne had no time [to] write to you, he is very sorry of [sic] leaving me & Rabnett. I accompanied him on board for about 5 hours bidding him farewell. Browne is going to the war at Galapoli [sic], perhaps never to see me again, whether he will I don’t know. May the Almighty God watch over him. Dear Sir, my Heart melts for him, I will pray for him with all my heart & I hope he may prosper over all his enemies. Dear Sir, I will never forget him as long as I live. I lost all my comrades except one, but I hope I see all their dear faces again… I watch[ed] the ship till it was out of sight when I was forced to return home very vex[ed] in loseing [sic] so good a comrade. He beg[ged] me to write to you [while] I was on board with him, he seemed very comfortable when I was with him but when I left him he felt very sorry.[27]

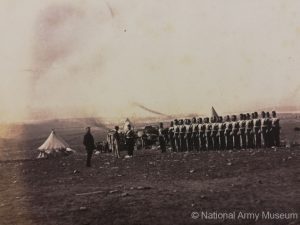

The 38th landed at Gallipoli and moved in June to Varna, on the western coast of the Black Sea (in present-day Bulgaria), where the British expeditionary force (the “Eastern Expedition”) and their French allies gathered. Browne wrote to Rabnett from ‘Camp Varna’ on 6 July – ‘when I write to you, always let Sharp read the letter, because I address the letter in a manner of speaking to both of you’ – and thanked him for passing on news of home: ‘I hope by the blessing of God to return again, so that I may be able to return your kindness in some way or other.’ He brought Rabnett up to date with his movements:

When we left Gallipoli, we encamped at Brullahar about 9 miles off, and while there our Regiment was employed all day in building Barracks, and every Regiment that go there does the same – [but] a part of them with a company of Sappers were building entrenchments. Two men came through our Camp and were exhibiting two brown bears to the soldiers. They passed the English without being found out, and while passing the French Camp the French soldiers discovered that they were Russian spies. I suppose they were shot.

Constantinople is one of the most splendid and fine cities I’ve seen. We have had a great many of our Regiment in the Hospital since we landed, and Loughman I hear is very bad. We cannot get any writing paper in this place, so I gave 2d to a chap in the Regiment for this very sheet. I do not care what it cost me, and I will be sure to send you word at every favorable opportunity if you answer some of them…

I should like to know if Diplock & Dalton is [sic] in Chatham, if so, give my kindest love to them… [Tell Agnes] that I am in good health since I last wrote to the Foundling…

It is rumored [sic] here that there is peace, and that we are going home, but I don’t believe it. The English and French are moving further on to the Russian Principalities every day, and I expect that our Regiment will follow them shortly.

My Instrument has had a queer damaging such as you have not seen before. I did not get anything for it, but I got 7 days confined to camp with about 20 more for bathing in the heat of the day. It is coming very hot indeed. My face got sore burnt…

[I]f there does be War, I really hope by the mercies of God that after the Battles are over … you may see me return, I don’t say with honour, but merely with my safety.[28]

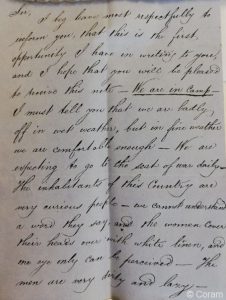

Daniel Sharp took the peace rumours seriously: ‘Browne has written a great many times to me and Rabnett… [H]e complains of the country being too hot, he is in perfect health at present. Some say at Varna that they will not fire a shot, they say that there is to be peace and the soldiers will come home very shortly which I hope is true…’[29] Browne’s last known letter to Brownlow came from ‘British Encampment, Near Varna’. ‘We are in Camp,’ he proclaimed, where ‘we are badly off in wet weather, but in fine weather we are comfortable enough.’ The local Turks are ‘curious people – we cannot understand a word they say, and the women cover their heads with white linen, and one eye only can be perceived’ and the men were ‘very dirty and lazy’. He himself was ‘in excellent health’. They were ‘expecting to go to the seat of war daily’.[30] The regiment arrived in the Crimea on 14 September and took part in the Allied victories at the Alma (20 September, when the 38th had no casualties) and Inkerman (5 November, a more substantial involvement), earning Battle Honours for both.[31]

The British and French proceeded to besiege the main Russian naval base at Sebastopol and it was in the British camp outside Sebastopol that Augustus Browne died on the last day of January 1855. This occurred during the winter lull in fighting and Browne, still a mere boy of seventeen, died of one of the illnesses which afflicted many soldiers during the siege.[32] Three weeks after his death, his Corporal wrote from the ‘Camp near Sebastopol’ to describe Browne’s fate. Browne ‘came out with the Regiment to the seat of war… I am now sorry to say you’ll never hear from him again, he is numbered with the many who have breath’d their last & are laid in a foreign grave. After a long & severe illness of about four weeks with Dysentry & no remedy or nourishment being given him he grew worse, he linger’d on till Nature was unable to hold out against it any longer, he died on the 31st of January 1855.’ Corporal Williams went on to express his sorrow about the loss of ‘a nice, quiet, willing lad’ and to suggest a degree of dissent regarding a campaign which was costing so many lives and leaving him in despair (there was ‘no hope … for death seems inevitable’):

Much pitied and regretted by his comrade Band’s Men, he was a nice, quiet, willing lad & would have made a good Soldier & Musician had we remained in England, but unfortunately for him & many others we came out too soon & the consequence was they met an early grave. He was unable to endure the trials & hardships of so severe a Campaign as this. Having to do night duty & heavy fatigues, which stronger men could not bear, was too much for one so little experienced as a Soldier; trying to do his duty which was beyond his strength threw him on a bed of sickness from which he never recovered. He is the third of our band we have lost by death, nearly all the men that came to the Crimea with us are dead. I can safely say there is not 150 men (not including Officers) with us at present that landed on the Crimea,* between deaths & illness they are all gone, all the old familiar faces have disapeared [sic] from our view, & the new ones that comes [sic] in their place, I am sorry to say, are disapearing equally as fast. God only knows how this will end or who will live to see the end of it, if we escape death by illness we cannot escape it at the Cannon’s mouth, we’ve no hope of the future, for death seems inevitable. God is our only hope & strength now for it is He alone that can save us.[33] * Our strength was 850 when we landed on the Crimea.

Over three years later, Secretary Brownlow laid claim, on behalf of the Hospital, to Browne’s campaign medal and any property left by the unfortunate boy:

Augustus Browne a Boy of this Establishment enlisted on the 27th [of] August 1853 in the 38th Regiment of Foot as a Musician (No. 3386) and died at the Camp near Sebastopol on the 31st of January 1855.

As the Governors of this Hospital stand in the place of parents to this Boy, I beg, on their behalf, respectfully to claim the medal to which Augustus Browne would have been entitled for Service in the Crimea, in order that the same may be deposited in the Museum of this Establishment with a record of the fate of a most exemplary youth. Shd. Augustus Browne have died possessed of property I claim that also.[34]

The Army duly sent the Hospital ‘£2.14.8 together with a medal of 3 clasps for Alma, Inkerman, and Sebastopol for the Services of the deceased in the Crimea’ and the money was paid into the Hospital’s Benevolent Fund for distressed former Foundlings.[36] A certain amount of scorn was poured on the Crimea medal by those (like Punch) who deprecated its inadequacy and irrelevance, and officers in the Crimea generally believed that it was ‘a vulgar looking thing’ with clasps like decanter labels.[37] It surely meant more to Brownlow, despite the business-like tone, for the medal honoured a boy he had known and come to value as a ‘most exemplary youth’. Browne’s letters do show him to have been a very likeable and estimable young man, and, of those boys who corresponded with the Hospital, he possibly had the most developed sense of family, constantly expressing attachment to Rabnett, Sharp, Diplock, Dalton, his ‘sister’, Soley, Twiddy, Brownlow and many others. It is chilling to think that almost all of the former Foundlings who were to fall in war – including 58 in the world wars – had no families to grieve for and remember them, no-one, that is, but their fellow-foundlings and the Hospital servants who had brought them up.

Rabnett and Sharp

On 5 April 1855, Captain Daniel, with ‘vacancies for 15 Drummers’ in Browne’s former regiment, wrote to ask Brownlow if there were any ‘Boys between 14 and 16 Years of Age in the Establishment under your Command’ – an interesting expression – ‘who wish to volunteer for the 38th Regiment for the purpose of being trained as Drummers or Musicians’ and was told by Brownlow that ‘at present we have no Boys old enough for the 38th Regiment’.[38] The 38th remained at Sebastopol until June, suffering huge losses, with 489 dead and 283 invalided home; it landed back at Portsmouth on 21 July 1855.[39]

Unfortunately, Augustus Browne was not to be the last casualty among the first wave of enlisting bandboys, for John Rabnett did not live through Britain’s second major military involvement of the 1850s, the Indian Mutiny. The Duplicate of Attestation in the Hospital archive contains some of Rabnett’s personal details and the document, which was not particular to one regiment, is also revealing of the procedure of the British Army. He enlisted in the 38th at Brompton Barracks, Chatham on 27 August 1853 and was required to sign the Attestation between one and four days later, before a magistrate, when the Articles of War were read to him and he took the Oath of Allegiance and Fidelity. He was 14 Years and 7 months old and 5 feet 4¾ inches tall (Complexion Dark, Eyes Grey, Hair Light Brown). Under ‘Trade or Calling’, he was described as a Labourer, he was not an apprentice, not married, and he had no physical Disability or Disorder. He had received an enlistment bounty of Two Pounds and he agreed to serve for thirteen years and 5 months, ‘provided Her Majesty should so long require your services, and also for such further term, not exceeding Two Years, as shall be directed by the Commanding Officer on any Foreign Station’. This was longer than the normal period of service: ‘This blank to be filled up by the Justices with Ten Years for Infantry and Twelve Years for Cavalry or Artillery, or other Ordnance Corps, if the person enlisted is of the Age of Eighteen Years or upwards; but if under that age, then the difference between his age and Eighteen is to be added to such Ten or Twelve Years, as the case may be.’[40]

Both of the boys who entered the 38th Regiment with Augustus Browne, Rabnett and Daniel Sharp, seem to have encountered difficulties at the beginning. Brownlow told Sharp on 19 September 1853 that he was ‘most happy to hear of your welfare – but I advise you, as a friend, not to commence Life by borrowing money. Do without any little matters [sic] rather than do that. It is sure in the end to lead you into trouble. I cannot take out your money from the Bank,’ Brownlow continued, ‘but I have requested Mr Reine [the Steward] to send you some working clothes. If there are things the Band Master [of the 38th] thinks we should supply you with he will write to me I am sure.’ This letter also discussed (but did not elaborate on) Rabnett’s behaviour: ‘I regret to hear that Rabnett has got into trouble. If he is discharged from the Band, he must go into the Ranks – here he will never be received again except as a good boy.’[41] Sharp asked for money (his own savings) in January 1854 and in July was ‘greatly in debt’ through having to buy uniform and kit, ‘and I hope you [Brownlow] will relieve me from this debt … because you are my only friends…’[42]

Rabnett wrote several times to Brownlow, first to say that, pending his first wage, ‘because I do not draw pay, I am in debt’, and then to thank him for the money which ‘got me out of debt’; he promised that he and Sharp would strive to ‘keep out of trouble, and out of debt’. Sharp said that both were ‘quite well’ when he wrote in September and October 1854, and he added some news from the war: the Colonel of the Regiment ‘died lately of the Cholera, which has not abated yet at Turkey. Almost all the British troops are at Sebastopol waiting for action. A draft is going out to join the Regiment in Turkey.’ He expressed no desire to be part of it. Towards the end of the year, Rabnett was ‘very bad off for shirts’ and asked Brownlow to ‘send me a couple… Sharp sends his best respects…’ Rabnett also revealed (in August) that he thought he was ‘going out to the Regt.’ in the Crimea ‘as a buglar [sic]’, but this did not happen.[43] Sharp’s final letter in 1854 showed his continuing dependence on the Hospital: having applied for leave to go to the Hospital at Christmas, and been refused by the regiment, he asked Brownlow ‘to send me a small sum of money for to spend the Christmas holidays with and I would be exceedingly pleased if you send Rabnett a Christmas box… We have no such merry days here as we did there at the Foundling…’[44]

Sharp reckoned at the beginning of March 1855 that it would soon be his ‘turn’ to go to Crimea – ‘I trust in God that I shall return home again’ – but, when a draft was held at Walmer Barracks (Kent) to choose 200 men and two drummers ‘for the seat of war’, it was John Rabnett who was chosen. His comment that ‘I must go sometime or other to fight and do my duty’ suggests a stoicism that is surprising only because it came alongside his expression of sadness over Augustus Browne’s death.[45] Most of the regiment had returned from the war by the time the decision to send out a second contingent was taken; Rabnett finally departed in August after writing of the ‘hope I shall return to see you [Brownlow] and my dear friends and comrades. I will look to heaven for my protection.’ The prospect of danger made him pensive and maudlin, recalling ‘the tricks and the mischief’ he had done at the Foundling; ‘I feel sorry for it, it makes me wish to come back [but] it is of no use wishing to come back for that is what I cannot do.’ His priority, however, was to have Brownlow send him money to buy ‘a shell-jacket and several other articles’ which would be ‘of great service’ to him in the field.[46] Sharp had him ‘laying at Malta’ in mid-September, a time when Sharp himself, perhaps fortunately, was too ill ‘to blow any instrument’ and, presumably, to be considered for service in the Crimea; he was ‘very glad to hear the good news about the taking of Sebastopol’ on 9 September.[47] Rabnett did not write until December, when his letter must have raised fears that he would share the same fate as Augustus Browne:

Camp near Sebastopol

Dec. 13th 1855

Respected Sir,

I now write to you these few lines to let you know that I am laid up in Hospital very bad indeed. The meat that I get for my dinner is dirty and the bread is almost as salty as the salt itself. I have had a few hardships since I have been out here. I have been down in Sebastopol three or four times to carry wood up to our camp which is about 4 miles and I would not be allowed to fall to the rear to rest myself and I was one time very near dead. I was taken to Hospital but I survived. A soldier[‘s life] do not agree with me…

J. Rabnett

Dr[ummer] 38th Regiment

3rd Division

Camp near Sebastopol

Crimea

P.S. This piece of money that I have enclosed is a Turkish coin. I think that it will be a bit of curiosity to you as there is not much Turkish money in London. Dalton and Diplock wishes [sic] to be remembered to you and to all enquiring friends, they are both well and in good health…[48]

It would appear that the band boys who went to war were subjected to rigours which strained the physical resources of adolescents, especially when they were used not so much as soldiers (narrowly speaking) as labourers (or pack-horses). Sharp ‘got 3 letters from Rabnett since he has been in the Crimea and I am very sorry to say that he has been afflicted with the fever & jaundice and now he has got three or four ulcers on his leg which I am very sorry to hear. There is every prospect of peace in the Crimea…’[49] Rabnett was in better form in March 1856 when, sitting ‘upon my blanket and rug which is my bed’, he wrote again from ‘Camp near Sebastopol’. Peace was in the air as the antagonists met in Paris to bring the war to an end:

We are at rest now for one month till the conference is broke up and then if we hear a shot fired we will know whether their [sic] is peace or war. I was on guard last Sunday week in Sebastopol and I had a very good view of their batteries and forts that they have on the north side and they are as thick as if they were houses. The Russians would come out of the batteries and stand in a row and give three cheers. Sometimes they would sing and other times they would form a ring and dance. I am very glad to state in this letter that my health is a great deal better than it was when I wrote last. Diplock and Dalton wishes [sic] to be remembered to you and to all their friends. Please to remember me to all enquiring friends. I must now conclude as the letters are being gathered to go to Balaklava.[50]

The main body of the 38th went to Ireland after the Crimea. In March 1856, Sharp briefly returned ‘quite safe’ to Walmer and, ever dependent, asked Brownlow to send him ‘a few shillings to pay my passage to London’ and the Hospital, adding in April, writing to Miss Soley, that, ‘I daresay you have heard that peace is proclaimed and I hear that there is to be great illuminations in London. I have written to Rabnett and sent your dearest respects to him…’[51] Rabnett and another bandboy committed some sort of offence before leaving the Crimea (or on the journey home), writing from Aldershot on 30 July that he ‘arrived home safe and was directly put into the guard tent till the next morning and then brought before the Colonel. He told me it was the letter [from the Hospital] that kept him from punishing me… The other Drummer my comrade was forgiven the same as I was. We are very thankful to you and also to Mr Brownlow for the note.’[52] He met Sharp at Aldershot and they awaited orders for Ireland, where he feared that the soldier’s life would test him again:

[W]e do not know the day we will go but the next time I write to you I think it will be in Dublin but I hope not, as I would not like to go there on account of there being so much duty, trooping twice a day and fields [exercises] once every day and likewise General field days 3 times a week in heavy marching order, with a knapsack and kit weighing 56 lbs and besides a drum which I think will be very hard for both me and Sharp.[53]

Both boys went to the Curragh Encampment in Ireland, from where Rabnett reported that he and ‘very near all the regiment’ failed a kit inspection just after arriving and he asked, in vain, for the Hospital to send him ten shillings ‘to help me in getting a kit’. But he and Sharp were in ‘good health’.[54]

After a long sojourn in Ireland, the 38th set sail for India on 31 July 1857, bringing Rabnett and Sharp. The Indian Mutiny, the greatest moment of crisis in the entire history of the British Empire, had begun at Meerut on 10 May 1857. Within a month, rebels, both Hindu and Muslim, were in control of a large swathe across northern India. Thousands of reinforcements were sent out from Britain, but the situation had greatly improved, thanks to the majority of Indian soldiers who did not rebel, before they arrived and entered the field. The 38th disembarked at Calcutta on 22 October and helped to defeat the rebels of the Gwalior contingent at Cawnpore in December, and, as part of the Third Infantry Brigade, it took part (with one man killed) in the famous Relief of Lucknow in March 1858.[55] John Rabnett, however, was ‘accidentally drowned’ in the River Ganges, at Benares (Varanasi), on 18 December 1857, 12 days before his nineteenth birthday. He had survived the horrors of Crimea only to fall at the next obstacle.[56] Only Daniel Sharp, then, of the three who joined the 38th in 1853, survived. The 38th remained in India after the Mutiny, and Sharp earned ‘the good conduct stripe’, but in December 1862 he was ‘sent from his regiment in India as sick’ and, six months later, Brownlow supported his transfer ‘into the Coldstream Guards for the Band of that Regiment in which several other Foundlings are now serving’.[57]

Terms and conditions

Some quite little band boys were involved. Samuel Dalton, at 14 years and 4 months, was 4 feet 10¼ inches tall and weighed 7 stone 2 pounds, but Henry Graham, a full year younger at 13 years and 4 months, stood at only 4 feet 6½ inches and, ‘very thin but a healthy boy’ (Reine), weighed just 5 stone 2 pounds. Offering them to a regiment in February 1854, Brownlow wrote that, ‘These two boys are desirous of entering and our medical man does not see any reason why they should not do for the service. We have two others but they have had no instruction in music. They are both 14 years old.’[58] In the event, the Recruiting Department decreed that ‘Henry Graham is at present below the prescribed Age for admitting Boys into the Army; therefore his Enlistment cannot be sanctioned until he has completed his 14th Year.’ He remained in the Hospital for another two years, when he was apprenticed to a gas fitter.[59] It was George Diplock (almost fifteen, having first been apprenticed to a Woolwich pawnbroker in July 1853) who entered the band of the 18th Royal Irish Regiment of Foot with Samuel Dalton in March 1854.[60]

One indication of the Hospital’s continuing interest in the welfare of the boys, for whom it was legally responsible until the age of majority, twenty-one, was the General Committee’s order, ‘That the expenses of the outfits of the two boys who have recently enlisted in the Band of the 18th Regt. of Royal Irish now at Chatham be defrayed out of the Funds of this Hospital, and that in future outfits be allowed with Boys under similar circumstances.’[61] When the regiment returned this clothing, and the Colour Sergeant commented that the two boys ‘get on remarkably well but they are a little downhearted at being in Debt for their Kit,’ Brownlow was clear that the boys would not be liable:

I beg to acknowledge the return of the Clothing of the Boys Diplock & Dalton.

I am glad – very glad – to hear so favourable an account of them, but it is contrary to our wish that they should be in Debt. Pray tell me the amount of cost of their Kit & I will send you a Post Office order for it.

Remember me to them and say that their continued good conduct will be a source of happiness to me at all times.[62]

Diplock subsequently listed and priced the required items of kit: the knapsack at 12s 6d was the most expensive item, ‘1 pr Boots’, ‘Summer Trousers’ and a ‘Shell Jacket’ each cost 7s 6d, and the total was £2.14.6½ – ‘and if we did not enlist as soon as we did we would have had to pay 7s 6d for a pair of Black Trousers. Dalton’s Kitt [sic] is the same as mine.’[63]

Most boys who entered the military were not indentured. Foundling apprentices and their masters normally signed indentures which set out their obligations in some detail, and the Hospital was assiduous in monitoring apprenticeships and holding errant masters to account, often having recourse to litigation. For the boys who enlisted, however, the Apprenticeship Registers before 1859 generally left the column for ‘Date of Indenture’ blank and the bundles of preserved indentures do not include any for soldiers (or sailors). As Twiddy found in relation to the Navy (see below), conditions of service in the military had been set out some time before the Foundling took an interest, they were not negotiable, and his comment regarding a band boy wanted by the Royal Horse Guards, that he was ‘to be entered therein under the usual form of enlistment’, referred to the Army’s usual form, not the Hospital’s apprenticeship system.[64]

The only references to indentures in the 1850s correspondence – as in ‘Your Lordship [Lord Carrington, Royal Bucks Militia] is doubtless aware that the clothing and entire support of the Lad [Arthur Lane] would fall upon Your Lordships [sic] during the term of the Indenture’ – related to special arrangements, described below, for service with militia regiments and not the regular, globetrotting Army.[65] Army boys, unindentured, locked into institutional life and frequently deployed in foreign lands, could not have received the same degree of monitoring or protection as other apprentices. Initially, except in relation to one boy, Thomas Piper, the annual questionnaire which asked masters about the conduct of apprentices – Honest? Sober? Truthful? Obedient? Industrious? Respectful? – was not submitted to the Army, as was made clear in Brownlow’s analysis of the returns.[66] But the surviving evidence does suggest some degree of continuing contact and support. This involved financial support, for example the money, as well as books and items of clothing, sent to Rabnett and Sharp, and the kit money for Dalton and Diplock, and intervention in relation to a particular concern, the fate of any boy whose regiment was disbanded, which was a common occurrence at the end of a major conflict like the Crimean War.

Brownlow naturally showed less interest in the fortunes of boys as they approached the age of majority. James Keane was an unsteady young man of twenty who in 1854 quit his apprenticeship after five years and joined the Army (the 19th Regiment of Foot) as an ordinary soldier. He asked Brownlow to support his transfer to a regimental band ‘as a Bandsman is a king to a private soldier in every respect’ –sadly, he did not explain this interesting comment – but Brownlow told him he was ‘assured by competent authority that it would be useless for me to write in the way you propose to get you into the Band, you must be content in the state of Life you are in’ unless you achieve promotion. ‘You have excellent abilities and I have no doubt you will turn them to account.’[67]

The Royal Bucks Militia, ‘disembodied’ in 1814, was re-embodied in 1854 for service in the Crimea.[68] Lord Carrington, the regimental commander, asked for Arthur Lane to be apprenticed ‘to learn a trade’ and to play in his band without being a fully-fledged member of the militia:

I am told there is a boy in your excellent Institution who is desirous of being apprenticed to learn a trade. It is a boy who plays the first Clarionet. I am willing he should be apprenticed to me for seven years & I will take care that he receives the best instruction in any trade which he may select. He would also have to play in the Band of my Regiment of Militia, but this would be compatible with the other object, & of course he would not be attested as a Militiaman… I need not add that every care will be taken of him & that he will regularly attend School.

‘And, Arthur Lane, the Boy referred to, having been called in & questioned, expressed a desire to be apprenticed to Lord Carrington in the manner proposed’; the General Committee resolved, ‘That the wish of Lord Carrington be complied with & Indentures prepared accordingly.’[69] Lane quickly settled in:

I am 1st Clarinet in the Royal Bucks Militia Band. I write my own music and play the Psalms in the Chapel of a Sunday.

I like my situation very much indeed… I have plenty to eat and 6d per day to do what I please with… I am not sworn in yet but I have got my uniform.

It is my desire to be a good Clarinet Player, to be able some day to get my living by it.

Remember me to the Band Boys and tell them how I am getting on.[70]

I am getting on very well indeed at present. We are still at Windsor which is a very pretty town. Our Band has had the privilege of playing at the Castle 2 or 3 times a week which is more than any other Militia Band has done.

Our music is much more difficult than the music I used to play at the Foundling. I am now used to the F sharp key and I am very fond of my Instrument…

I have taken your advice in practising the scales and the difficult pieces of the 1st Clarinet parts, and will continue to do so for I find myself getting on more and more every day.

I continue to like my situation. I am not sorry for coming in the Militia but I am living very comfortable and happy.

Remember me to the Boys, more particularly to the Band because perhaps they might wish to come in the Militia so that they might know how I like it myself.[71]

In a third letter, he advised that Foundling Band boys entering the military should ‘keep up Music and not let the name of a Soldier keep them from being Musicians. The more I improve the better I like my situation.’[72] In 1856, however, when the regiment was disembodied again, he subsisted on ‘the few shillings which Lord Carrington allows me’ and complained that his commander had done nothing for him ‘in the way of putting me to a Trade’; he did not know if he ‘was ever bound to Lord Carrington as an apprentice… I should feel happy to be relieved from this situation, as I see no prospects of getting on with my Music and I am also afraid of involving myself into debt…’[73] Carrington was quizzed regarding Lane’s ‘present & future prospects’ and Brownlow sent ‘sincere thanks for the kind interest your Lordship have [sic] taken in this Boy’s Welfare’ – but he accepted that Lane would have to be returned (the Committee ‘are desirous of receiving him again into the Hospital’). It was Charles Godfrey, the Bandmaster who had been so critical in 1848, who rescued the situation by agreeing to take Lane into the Coldstream Guards.[74]

Dalton and Diplock

In November 1854, shortly after Samuel Dalton and George Diplock arrived at the Brompton Barracks at Chatham, Dalton wrote to say he was ‘getting on quite well at present’ and to thank Brownlow for money that had been sent down to him.[75] George Diplock, however, was ‘hard up’ and, knowing that Brownlow had put ‘bounty money’ in the Savings Bank for him, ‘I thought I would send for some, as I was in want of it.’ Brownlow explained that the Hospital had lodged money in the bank ‘as a reserve fund in case of necessity in after years, that is, when you become of age’, which sum would ‘only be given to good boys’ who had volunteered from the band.[76] As noted above, Dalton and Diplock were stationed with Augustus Browne (at Chatham) and the senior boy duly promised Brownlow ‘that as I am so near situated with them, that I will use my utmost endeavours to lead them in a straightforward and upright manner of life, and, by the help of God, they may be able, bye & bye, to stimulate others, in our Saviour’s words, to “Go, and do likewise”.’[77]

Dalton and Diplock were received by the 18th as part of the recruitment drive prompted by the Russian war and the order to go to the Crimea duly came in December 1854. Two days before departure, Diplock was ‘sorry to think that the order for us to start came so soon, but there is one above who sees, guides, and judges all, and he alone can guard me across the sea, and in a foreign land, as well as at home, if we trust in him what need we fear[?] I do not know exactly when we are going but we expect it daily, we have orders to be ready to turn out at one minute’s notice, but I am sure to know the night before we go and then I will drop you [Reine] a note. But we will not forget you when we are abroad…’[78] The regiment, with both boys, departed on 8 December 1854 and did not see land until the 15th, when they passed through the Strait of Gibraltar, seeing the Rock ‘at a distance’. Diplock wrote that,

I am at this very moment sitting down on the Deck in full Dress writing these few lines. I have no more to say at present till I get on the Battlefield of Russia when I will let you know everything that occurs so do not write till I send you word again if God should spare me… Dalton is quite well.

Diplock apparently experienced a degree of trepidation as well as excitement. Other problems were more mundane: for ‘the first four or five days I was very sick but now Thank God I am very well’.[79] The regiment disembarked at Balaclava on 30 December. Joining Sir William Eyre’s brigade, which already included the 38th (Augustus Browne’s regiment), the 18th marched up to Sebastopol (‘a blizzard raged as they floundered through deep snow along a track, marked by the bodies of transport animals killed by starvation and overwork’ – Gretton), where even the relatively ‘well-fed, well-clothed, well-shod men of the XVIIIth’ struggled through the hardships of the exceptionally severe winter.[80] Dalton’s long-delayed first letter home, in May 1855, claimed that this experience was less difficult for the bandsmen, who were not required to go to the trenches, an advantage that had not been sufficient to save Browne:

I take a favorable opportunity of writing a few lines to you to let you know how myself and Diplock are getting on. Since I landed in the Crimea thank God I have had very good health. I have now shifted from Balaclava to the 3rd Division. The winter here was very cold and it was very severe on the men but it did not much matter with me as I had not to go to the trenches. But now as the weather is a great deal warmer great improvement [h]as been made, the men look more spirited, but one thing you could not here [sic], the birds singing the same as at home… This letter leaves me and Diplock in good health at present.

He appraised Britain’s French (‘a fine lot of men but in general not so tall as ours and not so stout’), Turkish (‘very dull looking’) and Piedmontese (‘low sized men and smart looking’) allies, and noticed ‘several Polish prisoners who have given themselves up to the English, and they gave great information to Lord Raglan’.[81] The Russians were ‘very good soldiers at their large guns, they are great fellows for throwing shell, but let them come and show us a field fight, and we will soon show them the difference’ – as demonstrated by a recent night foray when the Russians were quickly ‘hunted back’. He did not think that the siege had ‘done them [the Russians] much damage, there was a great many sailors killed and wounded, but the next time … I expect it will be better managed … and you may be sure there will be great cannonading.’[82]

On 18 June, the 40th anniversary of Waterloo, the French and British attempted to storm the two great redoubts which defended Sebastopol, the Malakhov (the French target) and the Great Redan (the British). Eyre’s 3rd Division, including the 18th and the 38th, ‘fought magnificently’ and this was the battle in which Captain Thomas Esmonde of the 18th was one of the first to earn the newly-instituted Victoria Cross.[83] Dalton, writing from ‘Camp before Sevastopol’ on 29 June, described this struggle (without claiming any personal role) but painted a picture, in the main, of ennui and impatience as the siege dragged on:

I received your [Brownlow’s] letter this morning with great pleasure which leaves [sic] me & Diplock in perfect health at present, Thank God. I suppose you heard about that affair which took place on the 18th June, our Regiment suffered loss that day [under] General Hare [Eyre] Brigadier General of the 3rd Division. It is reported that Lord Raglan died his morning. We expect a draft out every day now. There is nothing particular going on at present here, every one is getting tired of it, thinking of stopping here for another winter, wishing to go in every day to make an attempt to take the place. It is very curious weather here, some days very hot and other days very windy. There is [sic] different stories going about every day so that you don’t know what is true and what is not true. Now will be the question who is to take command of the allied army.[84]

I was telling you about the 18th June. The morning they made the attack they had great advantage of us [sic]. They were stationed on the top of a hill and while ours were advancing up the hill they [the Russians] were pouring down grape shot: we took the grave-yard, and some of them [the British] got into the Russian houses, and I believe they had fine furniture in them. The place [Sebastopol] is not so easily to be taken as some people think…[85]

The first volley of grape-shot accounted for one-third of the advancing British and both attacks (French and British) failed with massive losses; it was ‘not a battle but a massacre’, ending ‘in disaster and the needless sacrifice of many men’.[86] Some of Eyre’s men did defeat the Russians in the Cemetery and break into the suburbs of Sebastopol, as Dalton indicated, but they were outgunned and forced to withdraw.[87] It would be the conquest of these redoubts, with neither 18th nor 38th involved (and the French irresistible), which brought the fall of Sebastopol in September.

Dalton and Diplock had come through a dreadfully hard winter and were now facing the different but equally deadly challenges of the fighting season. They impressed sufficiently to persuade their officers to ask for more Hospital boys, Colonel Edwards himself writing from ‘Camp before Sevastopol, Crimea’ on 18 May 1855:

Gentlemen,

The conduct of Privates No. 3167 Samuel Dalton and No. 3168 George Diplock, now serving in the Crimea, as bandsmen in the Regiment under my Command, who were enlisted from the Noble Institution under your direction, has been so satisfactory, creditable alike to their training and education, as well as to themselves, that I am induced to hope that you will allow some more of their former companions to join them.

I will carefully watch over their welfare, and I think that advancement to well educated youths is beyond a doubt in the 18th (Royal Irish) Regt. – and though at first intended for the band (for which I apply for them), I will not allow their proficiency in music however great to stand in the way of their promotion.[88]

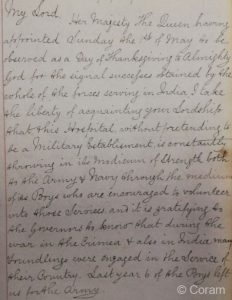

On 2 June the General Committee noted receipt of Edwards’s letter and ordered, ‘That Lt. Col. Edwards be informed that this Committee regret they have no Boys at present of a proper age for the Army.’[89] Brownlow and the Committee were aware that conditions in the Crimea were truly dreadful for the ordinary soldier, William Howard Russell’s reports in The Times having made a sensational impact (not to mention Corporal Williams’s harrowing letter regarding Augustus Browne).[90] But there is evidence that the Foundling’s leaders were proud of their former charges’ service. In a report (Objects of the Charity) written in May 1855, Brownlow described how ‘many’ boys had volunteered as soldiers and sailors ‘and are now fighting the battles of their Country in the Crimea, the Black Sea and the Baltic’, the latter the arena of naval warfare with the Russians. The sense of pride was even more evident when the Hospital joined in marking the ‘Day of Thanksgiving … for the signal successes obtained by the whole of the forces serving in India… [I]t is gratifying to the Governors to know that during the war in the Crimea & also in India many Foundlings were engaged in the Service of their Country. Last year 6 of the Boys left us for the Army.’[91] It is likely that, as with the 38th, the refusal was caused by the unavailability of suitable boys.

On 2 June the General Committee noted receipt of Edwards’s letter and ordered, ‘That Lt. Col. Edwards be informed that this Committee regret they have no Boys at present of a proper age for the Army.’[89] Brownlow and the Committee were aware that conditions in the Crimea were truly dreadful for the ordinary soldier, William Howard Russell’s reports in The Times having made a sensational impact (not to mention Corporal Williams’s harrowing letter regarding Augustus Browne).[90] But there is evidence that the Foundling’s leaders were proud of their former charges’ service. In a report (Objects of the Charity) written in May 1855, Brownlow described how ‘many’ boys had volunteered as soldiers and sailors ‘and are now fighting the battles of their Country in the Crimea, the Black Sea and the Baltic’, the latter the arena of naval warfare with the Russians. The sense of pride was even more evident when the Hospital joined in marking the ‘Day of Thanksgiving … for the signal successes obtained by the whole of the forces serving in India… [I]t is gratifying to the Governors to know that during the war in the Crimea & also in India many Foundlings were engaged in the Service of their Country. Last year 6 of the Boys left us for the Army.’[91] It is likely that, as with the 38th, the refusal was caused by the unavailability of suitable boys.

In April 1856, as the war drew to a close, Colonel Edwards wrote from the Crimea ‘testifying in the most satisfactory manner to the conduct of Privates Diplock and Dalton, Boys of this Hospital’. Prompted by their telling him of the Foundling’s system of annual testimonials (and rewards), he wrote that they had earned ‘high testimonials of their good conduct … in circumstances of peculiar difficulty, exposed as soldiers to several severe trials … which could only be overcome by the good seed you [the Hospital] have been the means of sowing, aided by God’s blessing.’ He went on to renew his application for more boys for the band and offered the prospect of service during a time of peace: ‘The Regiment is, I expect, about to return to England immediately, and will in all probability remain in England for several years, so that the youth of boys would not be against them … and they will have greater advantages than Privates Diplock and Dalton had, as they will have the benefit of their countenance and advice.’[92] The Committee resolved that ‘the Gratuity usually given to good Apprentices at Easter be awarded to the Boys Diplock & Dalton’ and Brownlow belatedly replied:

Some time ago the Governors of this Hospital had the honor of receiving a Letter from you of a gratifying nature respecting the boys Diplock & Dalton, & I should have replied to that Letter earlier but preferred waiting till the regt. had returned.

Should it not be inconsistent with your regulations & convenience we should be highly pleased to see the boys here & to present to them the rewards to which they have become entitled by their good conduct.

In the temporary absence of our Band Master, I am not at this moment able to say whether we have any boys qualified to join your regt. as musicians; but I am quite sure the Govs. would meet your wishes in this respect in preference to any other Applicant.[93]

The two boys ‘received the Crimean Medal with the clasp for Sebastopol’ and Diplock ‘hope[d] that the War will soon come to a conclusion so that we may soon return home again to England’.[94] The 18th left the Crimea in June and ‘landed in our native land once more’ in July. Diplock played in the band during the Queen’s inspection of the regiment at Aldershot and was clearly proud of its role in the war: ‘I cannot tell you exactly what she said, but she past [sic] some remarks on our old Colours about being torn so much’.[95] The Hospital asked Colonel Edwards to allow Diplock and Dalton to visit the Hospital and, ‘much pleased to have it in my power to continue my good report of these youths’, he granted permission.[96] On arrival in Dublin on 26 July, Diplock’s cheeriness (‘I can’t tell you much about Dublin at present but I think I shall like it very well’) was balanced by Dalton’s circumspect verdict that ‘it is a fine city but there was more talk about it than it really was… I did not see any place like London yet’ and perhaps genuine concern that the boys had failed in their mission: ‘Col. Edwards did not speak to us yet, he told us to fetch half-a-dozen [Foundling] boys. I don’t think he will be any way pleased when I tell him none of them were inclined to come.’[97]

A month later, Dalton and his comrades were ‘getting on very well’ and ‘about to receive our new Colors’ (with Sebastopol inscribed) from the Lord Lieutenant. ‘The old Colors are to be deposited in St. Patrick’s Church’ – meaning the Cathedral, where they still hang today.[98] The 18th then moved to the Curragh in Kildare, where the boys were in frequent contact with Rabnett and Sharp. In the autumn, Dalton and Diplock both wanted to spend their one-month-long furlough at the Hospital, with the latter’s reasoning – ‘They are all going… I would rather come, for I should feel very lonesome staying in Barracks without anyone to talk to’ – a painful reminder that these boys did not have the same family support as most of their comrades.[99]

A month later, Dalton and his comrades were ‘getting on very well’ and ‘about to receive our new Colors’ (with Sebastopol inscribed) from the Lord Lieutenant. ‘The old Colors are to be deposited in St. Patrick’s Church’ – meaning the Cathedral, where they still hang today.[98] The 18th then moved to the Curragh in Kildare, where the boys were in frequent contact with Rabnett and Sharp. In the autumn, Dalton and Diplock both wanted to spend their one-month-long furlough at the Hospital, with the latter’s reasoning – ‘They are all going… I would rather come, for I should feel very lonesome staying in Barracks without anyone to talk to’ – a painful reminder that these boys did not have the same family support as most of their comrades.[99]

By this stage, with a number of former inmates carving out careers in the military, the Foundling Hospital and its boys had earned a considerable reputation. In July 1856, Godfrey of the Coldstream Guards approached Bandmaster Twiddy looking for ‘a talented Boy about leaving the Asylum [sic]. We are augmenting the Coldstreams, and I can assure you – without flattery – that I have the highest opinion of all I have heard and seen of your department and consider it conducted in the soundest principals [sic], much superior to anything of the kind in this Country.’ He cited another bandmaster whose ‘opinion was in strict accordance with my own. Mr. Mohr said it was impossible it could be better. He had not seen anything on the continent to excel’ the ‘juvenile tuition’ at the Foundling Hospital.[100] Godfrey took both Arthur Lane and, in September, Francis Stalman; the latter ‘recently discharged from the Royal Navy, [he] has enlisted in the regiment of the Coldstream Guards [and] is placed in the Band of that regiment under Mr. Godfrey.’[101] Samuel Edwards of HMS London also made the switch to the Army; by July 1856, he was serving with (and liking) the Scots Greys (heroes of Waterloo and Balaclava) at the Curragh in Ireland.[102]

When Lt. Col. John A. Vesey Kirkland was commissioned to raise the 2nd Battalion of the 5th (Northumberland Fusiliers) Regiment of Foot to help suppress the Indian Mutiny, he asked the Hospital for ‘a few Boys for the Band or Drums who may be inclined to enlist for the regiment under my command’. James Howard, Charles Rutland (the youngest, at 14 years and 3 months) and Matthew Wasdale were ‘permitted to enlist accordingly’ in October 1857. Wasdale failed the medical (‘he ‘was rejected by the Surgeon of the Regiment’) and went instead to the Royal Marines.[103] In January 1858, Kirkland’s request for ‘additional Boys for the Band of his Regiment’ was turned down: one asked-for boy was already employed in the Secretary’s office, another was not yet fourteen, and the other two, ‘if disposed to enlist at all’, did not wish to leave London (‘are not willing to go into the Country’).[104] Howard and Rutland went to India with Kirkland in 1858; they were too late for military action there, but the regiment’s later deployment to Mauritius, to deal with unrest among the indentured labourers from India, saw both Howard and Rutland dying, probably from disease, in March 1860 and October 1862, respectively.[105]

The Royal Navy

If the Army was the principal destination for the Hospital’s bandsmen, the Royal Navy, briefly, was not far behind. Samuel Edwards, who played the clarinet in the first concert in 1849, joined the Navy as a bandsman in September 1851, aged 14½: ‘Entered H.M. Naval Service on Monday the 23rd Sept. 1851 on board the Flag Ship London.’[106] Richard Hopkins (on the clavicor in that concert) had been ‘retained for instruction in Music under the Bandmaster’ until June 1852, when he joined the Navy as a bandsman; the Secretary was ‘enabled to place Richard Hopkins in the Band of H.M. Ship Monarch, lying off Sheerness’.[107] However, the Navy did not jump at the chance to receive band boys from the Hospital. In February 1852, Brownlow offered ‘a well grown boy here [Edward Hughes] aged 16 who is very desirous of entering the sea service. He has been instructed in Music and is able to play on most of the Wind Instruments of our Band’ (he played trombone alongside Browne in the 1849 concert) – but the first officer he approached said that there were ‘no vacancies for Boys in the Navy’.[108] In August 1853 (at the same time as the Army first took boys), Brownlow, on behalf of the General Committee, made a formal approach to the Admiralty:

I am directed by the Governors of this Hospital to state that from time to time several of the Boys of this Establishment are desirous of entering Her Majesty’s Naval Service, and to solicit the favor of the Lord Commissioners of the Admiralty affording facilities for their doing so [sic].

I need not add that the boys of this Hospital are trained to everything that is moral & excellent in conduct.[109]

The response was abrupt and by no means encouraging: ‘boys are not required in the Navy at present’.[110] Nevertheless, Brownlow explained to a Navy officer that, although there were no Foundling Hospital boys in ‘the Sea Service’ (he overlooked Edwards and Hopkins), ‘As we may have at some future time, I will thank you to inform me of the terms upon which you would receive them.’[111]

Richard Hopkins’s ship, the Monarch, was part of the fleet which accompanied HMS President, Admiral Morris’s flagship, to the Pacific. Hopkins described his ‘very pleasant voyage’ to Rio de Janeiro in November 1853; he clearly enjoyed the experience, despite having to endure an initiation rite (‘the usual custom … being shaved with tar’) on his first crossing of the Equator; they saw ‘plenty of flying fish and dolphins’ and ‘hooked a shark’, and he ‘had the pleasure of dining off the old fellow’s tail’. The evenings in Rio were ‘very cool and pleasant’ and they were ‘in no want of fruit. Orange[s] are as cheap as nuts in England. For three-pence, I got fourteen very good oranges. As for Bananas, yams, plantains, cocoa-nuts and melons, you can almost get them for nothing. We shall lay here about a fortnight and then sail for Valparaiso’ in Chile, a six-weeks journey (he estimated) which would take him round Cape Horn.[112] Hopkins was clearly taken with the exotic side of life in the Navy. From Valparaiso, he sent Twiddy an astonishingly polished (if slightly unctuous) letter – ‘after considering your kindness towards me, and the interest you still express in my behalf, I am induced to confess that my neglect in not writing is perfectly inexcusable… I trust, sir, that the vexation and trouble which I brought on you formerly is forgiven… [I]f you find any ungrammatical passages in my letter, you must make every allowance, as you are well aware that a line-of-battle ship is not exactly the best Grammar School in the World’ – in which he deprecated his captain’s ‘eccentric notions about music and musicians’ (imposing a German Bandmaster who did not ‘know a word of English and never arranged a piece of music in his life’!) and the way in which a Rossini opera was ‘murdered’ in Valparaiso’s ‘so-called Italian Opera House’ – but he was ‘getting on very well’ and obviously enjoyed visiting the region’s natural attractions and seeing ‘some of the most curious races of men to be met with on the face of the Earth’.[113]

In December 1853, the captain of the newly-commissioned HMS Princess Royal ‘applied for six boys of any age over 12 years, of the Juvenile Band of this Hospital to join his Ship as Musicians’. Bandmaster Twiddy was delighted to find that his musicians were held in high regard: ‘when Lieut. Crawford and Lieut. Jones heard Bandboys of this Hospital play, the other day, they were so pleased with their performance that they expressed their opinion that Lord Clarence Paget [their captain on the Princess Royal] would be glad to make up his entire Band with the Boys of this Hospital.’ Twiddy applied for information regarding ‘immediate pay, condition[s] & future prospects’ of the boys and was told that they ‘must serve as 2nd Class and 1st Class Boys’ – and be paid £9.2.6 a year and £10.12.11, respectively – ‘till the age of 18, when they are rated ordinary seamen, and serve as such, till the age of 21, when they become eligible for ableseaman rating’ and get paid £29.9.0 a year. But he was assured that the Hospital’s musicians might be rated as ableseamen ‘at a much earlier age’. Other ‘advantages’ deemed ‘peculiar to Bandsmen’ included the likelihood that they would be chosen and paid as servants by the officers; ‘Bandsmen are generally selected, as having more leisure time on their hands than the generality of the Ship’s Company, and as being, for other reasons, more suitable as Servants.’ Concern was expressed that the boys would not be recruited ‘as continuous men’: those joining ships – the Marines were different – were ‘not to be considered as forming a part of the permanent navy… The Boys will be thrown upon their own resources whenever the ship they may be serving in is paid off, and must depend on the chances of procuring a situation on board such ships as may be in want of musicians’ – but it was expected that as musicians, often in short supply (‘there has always been a great difficulty in procuring Musicians immediately when wanted’ – Twiddy), they would generally be successful in finding new berths. Boys, it was decided, would be allowed to join the Princess Royal ‘provided the act be entirely voluntary on their part’.[114]

On 14 February 1854, four boys, Richard Lawford, Francis Stalman, Edward Forster and John Down, were taken to Portsmouth and their names were ‘entered in that Ship’s Books as second class Boys’.[115] Lawford wrote from his ship at Spithead, where he was with the other three, that he was ‘quite well and happy and the rest as well’. ‘The men praise us’ and say ‘we are good boys… I like it very well indeed & the others as well… The officers take great care of us and we are happy for I could not hope for better.’ All four were paid 15s per month, but, stretching the meaning of ‘a little while’, Lawford claimed that ‘we will have double as much when we have been there a little while longer… Remember me to the Bandboys and tell them we have been practicing for the Russians’; he apparently meant artillery practice, at which he was an onlooker. He signed off with ‘Hurrah. Hurrah. Goodnight all.’[116] Stalman ‘like[d] the ship very much indeed, it seemed rather strange at first but now I am quite getting in the use of it… It is quite true what you [Twiddy] told the boys … that if they only keep a good character they are sure to meet with their reward, they have only got to be civil & obliging to all and also industrious. We are now preparing for the Russians. There are plenty of cannon balls, powder and also bullets… I expect you have some small ones in your band and I should like if you will send me the list of the bandboys…’[117] It is possible that these boys’ naïve enthusiasm influenced Brownlow and others, for on 4 March, days later, the General Committee resolved that, ‘The establishment of a Juvenile Band from amongst the Boys of this Hospital having been attended with important advantages in affording opportunities of placing them in Her Majesty’s Naval Service as well as in the Army, and its being the opinion of this Committee that it is expedient to extend these advantages as much as possible.’[118]

Lawford was highly excited as the Baltic fleet closed with the enemy, and he revealed that the musicians, whose instruments had not come yet, would have a role in battle:

I am quite well & happy and the others as well. We are near Copenhagen and we are expecting the Russians every day. Our fleet consists of 21 or 23 ships … and our ship looks the best of the lot… Tell the Band boys we have been to Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Germany, &c. We are going to take possession of a town in Denmark and the Russians are going to try to[o], we are almost at the place and I expect we shall get it… We practice for the Russians and we hand up from the magazine 60 cases a minute…[119]

The Princess Royal, with its four Hospital boys, fought the Russians in the Baltic, part of Admiral Napier’s inconclusive effort there, and then sailed to join the war in the Crimea. The Navy brought a total of six Foundling band boys to the Crimea (exceeding, then, the four who went there with the Army). In Constantinople, Richard Lawford met former Foundling Samuel Edwards (‘I have seen Edwards at Constantinople and he is coming up at Sebastopoole [sic] again’).[120] By January 1855, still on the 90-gun London, Edwards was a veteran of many battles, according to the dramatic account he sent to Brownlow:

We sailed from England on the 5th of November 1853 and little did I think that on the next year I should witness one of the hardest actions fought in the Crimea. I have witnessed all the actions that have been fought here, among which are the bombardment of Odesa, Alma, Balaklava, Inkerman, and the bombardment of Sebastopol, in which the fleets were engaged. Our ship was on fire twice, but we were the nearest ship to Fort Constantine. We remained under the fire of that fort for 5 hours and a half, till the admiral made our recall, just as the ship caught fire the second time. On [our] coming out, the other ships gave us three cheers which we returned by a broadside into the fort. We lost five men killed and sixteen wounded. We refitted and anchored off Sebastopol. That was on the 17th of October, the charter [Charter Day] of the Hospital, as the boys were sitting down to their dinner at the Hospital at the same time I was in action. I thought of that the same day while I was in action.

Fort Constantine was one of two Russian forts (the other was Alexander) commanding the entrance to the harbour at Sebastopol. Damaged by a ‘hurricane’ in the Black Sea on 14 November, when ‘two men of war were lost’, the London returned to Constantinople.

We have undergone a thorough repair and are now waiting our orders for to go up to Sebastopol again. I do not think that we will take the place before summer, it is very strong indeed. The weather is intensely cold here, we have had snow this last two months, every day it is just the same, it has a long winter and then it is very cold, and a short summer which is very hot, and that makes it so unhealthy a country. I also heard from Mackay that some of my old schoolfellows have gone into the Army. If they would take my advice they would go in neither service…

These cautionary words were written a week before Browne’s death at Sebastopol. Edwards asked Brownlow to let all his Hospital acquaintances ‘know how I get on and that I expect to see them when we reach our blessed shore never to hear of war any more’. This was ‘the sincere wish of

Samuel Edwards Bandsman

on board Her Majesty’s Ship

London

Constantinople’.[121]

Lawford, sent the bad news of Augustus Browne’s death by Brownlow, replied from Sebastopol (that is, from the Princess Royal offshore) that he was ‘very sorry to hear that Browne is dead for he used to be a very great friend of mine… They have commenced the Grand Attack on shore and we are expecting any moment the signal to be made [to] prepare for action and when we come back out of action if it pleases God to bring me out of it again I will write to you Sir again and tell you how we got on and what prizes we took and so on.’ He wanted ‘a few things sent out’ but asked Brownlow to delay sending them until he had written to say that they had ‘come away from action’. ‘It is a sad sight,’ he went on, ‘to see the fighting and a hundred men being killed every day and night so you must think what a sight it is but all for that [sic] we are all in good spirits thank God and are all quite well.’[122]