For a more rounded account of how the Peace Conference dealt with Yugoslavia, see ‘Yugoslavia’ elsewhere on this website.

Allen Leeper was a minor official who rose to be a significant player in the making of the settlement with Romania. It cannot be argued that he had the same importance in relation to Yugoslavia, and one could not write of ‘Leeper’s Yugoslavia’. But he was active and productive in the long process by which Yugoslavia’s frontiers were established and a study of his involvement sheds light on many of the troubles of the new state. His efforts, though low-key, amounted to a substantial contribution, which, unfortunately, made him one of the authors of a famous failure.[1]

Although not responsible for the creation of Yugoslavia, which predated the Peace Conference, the peacemakers in Paris had the task of settling the new country’s disputed boundaries with Italy and Romania, Serbia’s wartime allies, and with former enemies like Austria, Hungary and Bulgaria. Leeper co-authored, with Harold Nicolson, the memorandum of December 1918 outlining Britain’s objectives in the region and they backed Italy’s claim to the city of Trieste in January 1919.[2] Fiume, however, they would give to Yugoslavia. Leeper wrote of “the impossibility of artificially separating Fiume from Sušak & the Jugoslav hinterland”. “Fiume – with Sušak – contains a Yugoslav majority.”[3] Leeper might also have given the Yugoslavs some covert assistance: when they claimed the western Banat before the Council on 31 January, getting the better of Brătianu, it is possible that their Foreign Minister benefited from the previous day’s meeting with Leeper (“long talk with [Ante] Trumbić alone”).[4] When the Yugoslavs later proved less reasonable, Nicolson reacted furiously, as noted elsewhere (see ‘Yugoslavia’), but Leeper’s comment was more measured: “The demands made must be taken as expressing the maximum conceivable & as inspired in some cases (e.g. Trieste) rather by necessities of internal policy” – the need to stifle Slovene complaints – “than by the belief they will really be granted.”[5] He was less forgiving when Anton Korošec, their leader, publicly stated that Slovenes would “fight to the last man like lions for the smallest Jugo-Slav village” – language that Leeper considered “absurdly pugnacious & altogether regrettable”.[6]

The frontier with Hungary

From early in February 1919, Nicolson was preoccupied with his role as Technical Adviser on the Greek Committee, and Leeper became the lead official on Yugoslavia after an odd procedural twist. Italy’s Foreign Minister, Sidney Sonnino, was determined that Italy would be judge rather than plaintiff and, on 18 February, when Balfour raised the possibility of referring Yugoslavia’s claims to a territorial commission, Sonnino objected to allowing any such body to make recommendations about matters concerning Italy; only the Supreme Council (including Italy) could consider Italy’s claims. It was decided to confine the remit of a commission to other territorial issues relating to Yugoslavia.[7] Because the Commission on Romanian Affairs was already dealing with the Banat, where Serbia was a claimant, its brief was extended to cover Yugoslavia (“So our Rumanian Commission will now be also a Jugoslav one” – Leeper). Thus, the Commission on Romanian and Yugoslav Affairs was born and Leeper, Britain’s representative (alongside Eyre Crowe), was put to work on setting the new country’s frontiers (except that with Italy).[8]

The spectre of Serbian hegemony had arisen when allegations that Serbia illegally consumed Montenegro prompted Woodrow Wilson to comment that, “Some of the other units of Yugo-Slavia were saying the same thing, namely, that Serbia was trying to put them under her own domination rather than to associate them with her.”[9] This, remarkably, was the only occasion when the deep-seated flaws in the state were openly discussed at the Peace Conference. The matter did feature occasionally in private observations and Leeper did not appreciate its seriousness. When one Croatian politician expressed his people’s opposition to union with “oppressive and malevolent” Serbia, Leeper dismissed such “separatist movements” as “dangerous to the future of the peoples concerned” and inspired by either Rome or Vienna, accused the Croat of confusing the new kingdom (“in the government of which Croats & Slovenes have a fully equal share with the Serbians”) with “Greater Serbia” (“such as was formerly favoured by some of M. Pašić’s partisans”), and declared that “no encouragement whatever should be given to such mischief-making.”[10] A British visitor to Syrmia (Srem), north-west of Belgrade, found men “of an extreme Croat complexion” who wanted “a completely autonomous Croatia” within a South Slav federation. But Leeper, reflecting the illusions of the pro-Yugoslav enthusiasts, held that, “The idea of union is new & has already made great headway. While separatist ideas cannot be expected to disappear at once, they will, if the united Jugoslav state is helped & encouraged by us, be likely to lose all importance.”[11] The Western officials at the Peace Conference turned a blind eye to the country’s internal problems and focused their efforts on settling the frontiers, generally supporting Yugoslavia in its contests with the regional rivals.

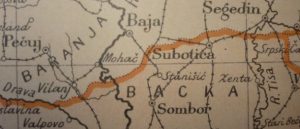

Leeper played a big part in partitioning the Banat, giving Yugoslavia one-third and Romania the rest (see ‘Leeper’s Romania’). He was one of the experts, alongside Charles Seymour and Jules Laroche of France, who gave Yugoslavia four-fifths of the Bačka. On the appeal of Bačka Germans who wanted to remain in Hungary, he simply commented that, “The Committee on Jugoslav claims unanimously decided to attribute practically the whole of the Bačka – including Szabadka & the  Szabadka-Zombor railway – to the Jugoslav state to which ethnic & geographic bonds unite it.”[12] He later conceded that, “The part of the Bačka assigned to Yugoslavia already includes 461,000 Magyars & Germans against 185,000 Slavs.”[13]

Szabadka-Zombor railway – to the Jugoslav state to which ethnic & geographic bonds unite it.”[12] He later conceded that, “The part of the Bačka assigned to Yugoslavia already includes 461,000 Magyars & Germans against 185,000 Slavs.”[13]

Regarding the Baranja, where both Germans and Magyars vastly outnumbered Slavs, Leeper and Seymour argued that the Serbs had no ethnic justification for their claim to land north of the Drava.[14] Josip Smodlaka of the Yugoslav delegation visited Leeper on 20 March and “argued very well” that “neither ethnically[n] or economically does the Drave form the best frontier between Hungary & Croatia… Good as was Dr. Smodlaka’s reasoning there seems no cause to regret the decision of the Committee.”[15] Yugoslavia would be given the Slav-majority area south of the river, but most of the Baranja was to remain in Hungary. To the west, the French and British successfully proposed that Medmurje, where the Slovene majority was overwhelming, should be put into Yugoslavia.[16] But the Commission was persuaded by the Americans to leave more ethnically mixed (Slav and Magyar) Prekomurje with Hungary; this decision was undone in May when the Americans agreed to give Prekomurje (slightly reduced) to Yugoslavia.[17]

The frontier with Austria

Further west, in Lower Styria and Carinthia, where the frontier between Yugoslavia and Austria had to be defined, Leeper and most of the Allied representatives united against Italian efforts to allow Austria, the former enemy, to retain territory claimed by Yugoslavia. Despite its 84% Austrian-German majority (in the census of 1910), Leeper called Marburg “un centre de vie slovène” and France’s Le Rond argued that most of the citizens were Germanised Slavs. The Italians were isolated when the Americans opted to give Marburg to Yugoslavia in return (until the change of mind in May) for leaving Prekomurje in Hungary.[18] However, Leeper could not secure Klagenfurt, the capital of Carinthia, for Yugoslavia because the Americans believed that the majority even of the Slovene inhabitants wished to remain part of Austria. On 8 March, he observed that the Klagenfurt question was “a tough nut but I hardly see how the Jugoslavs can fairly have it, though I insist they shall have Marburg.”[19] In the end, “a certain amount of patience and a great deal of tact” (Leeper) yielded a compromise by which the French, British and Americans agreed to hold “an inquiry or consultation” to determine the “real feelings” of the Slovenes – the origin of the Klagenfurt plebiscite. Writing to his brother, Leeper expressed his exasperation with the Italians, who contrived constantly “to safeguard their rather ricketty position founded on the Treaty of 1915” and to oppose Yugoslavia by courting her enemies:

They are remarkably naif on the subject, and though it is sometimes rather boring to us and wastes a good deal of time, it amuses us very much to listen to the elaborate dissertations on the [influence of] the principles of the New Testament on President Wilson with which they introduce their rather bald statement of Baron Sonnino’s views. However, from the point of view of a friend of Italy, it is all rather sad.[20]

In the Council of Foreign Ministers in May, deciding the frontier with Hungary proved straightforward, but Leeper knew that settling the Austro-Yugoslav border “will be infinitely more difficult as the Italians did not allow our report to be unanimous”.[21] The Italians wanted to leave the heavily Slav Assling Triangle with Austria to prevent the Trieste-Vienna railway line going through Yugoslav territory; when Sonnino unexpectedly agreed to the matter being examined by the Commission, Leeper was again in the thick of the action: “We had a great struggle & everyone was very difficult all round.”[22] As noted in ‘Yugoslavia’, Harold Temperley, Leeper’s colleague, proposed on 9 May to draw a line along the crest of the Karawanken mountains, to a point near Tarvis, to leave the area north of this line (the northern part of the triangle) with Austria, but to delay a decision on the land south of the line. He “filled Leeper up with this” – Leeper, more than a cipher, had it that he “got back at 11 & worked with Temperley & Gen. Mance [the War Office’s railways expert] on the morrow’s agenda” – and Leeper “promised to instruct Sir E Crowe in time for the next meeting at 9 a.m. the next day”.[23] Leeper claimed the plan as his own (“my draft was adopted”) and Nicolson, too, thought it was “really the work of Allen Leeper”.[24] In the Commission, the Italians “grew wilder and wilder in their protests” and,at the end, “left very sorrowfully”.[25] Balfour, “coached” on the plan by Crowe and Leeper, told the Foreign Ministers on 10 May that “we cannot hand over thousands of Slovenes to an enemy [Austria] without very grave reasons”.[26] Sonnino protested furiously – the Slovenes, so recently soldiers in the Austro-Hungarian army, were Italy’s enemies – before suddenly giving way. Temperley was proud of “the great victory won today” and Leeper hoped, too optimistically, that this “great triumph” might “prove the starting point for a real settlement of the whole Italo-Yugoslav question on proper lines. We were most delighted.”[27] Of course, the plan did not give the triangle to Yugoslavia; the decision was merely postponed.[28]

The Klagenfurt plebiscite

On 12 May 1919, Leeper enjoyed telling his brother that he had had his “first conversation with Ll. G.. I don’t suppose for a moment he knew who I was but I had to feed him with maps & explain things.”[29] It was the Klagenfurt question which now came to the fore and Leeper found himself very much at the heart of the action. After the Council accepted the principle of a plebiscite on 12 May, it was to Leeper that the Yugoslavs brought their alternative proposal to partition the Basin, splitting it with Austria, “without plebiscite”. Ivan Žolger, the leading Slovene in the delegation, opposed holding a plebiscite in “an area which had been within German [meaning Austrian] occupation and subjected to the most energetic German propaganda… [I]t was better to secure half than to risk losing all,” he told Leeper.[30] If this suggests that Leeper was an important contact-man for the Yugoslavs, this was evident again when Josip Smodlaka (a Croat) told him on 16 May that the Serb and Croat delegates “fully shared” Slovene concerns and consented to the Adriatic talks then being held by Colonel House “only on condition” that Klagenfurt’s partition should be agreed.[31] But Leeper was also an advocate, for he took the “new & very interesting proposal” on Klagenfurt to Laroche and Johnson and believed he had “got the French & Americans into line”.[32]

The Italians initially opposed the partition plan in the Commission because the Trieste-to-Vienna line would be cut: “This morning a stormy Committee with the Italianissimi in good form.”[33] Balfour’s stance was interesting from a Foreign Secretary: “The Italians make me sick, perfectly sick – they are worse than the Fr[ench].”[34] Leeper felt that, “The Yugoslav affair was only half successful. The Italians are, conditionally, coming round but the Americans make great difficulties – perhaps not insuperable – about cutting the Klagenfurt basin.”[35] There was division, in fact, between Douglas Johnson, who backed the partition plan, and Charles Seymour, who would let the people decide, but Seymour won the first round when Wilson agreed with him and the Council decided on 29 May to proceed with a plebiscite.[36] This followed an uproarious Council session on 27 May, when Lloyd George and Clemenceau ridiculed the Italians during what even serious-minded Leeper called a “very amusing meeting”.[37] Leeper was one of the officials who crouched on hands and knees around a map on the floor and heard Wilson present the Council decision for a plebiscite.[38] He proceeded to the Commission and was pleased “that we were able to get the final territorial clauses of the Austrian treaty through our Committee, this after a great wrangle with the Italians … rather a triumph.”[39]

Through all this, Leeper was merely a minor official who had less influence on decision-making than his American counterparts, Charles Seymour and Douglas Johnson, not to mention Harold Temperley. Appropriately enough, he was a little starstruck: “Johnson (U.S.A.) took me to Wilson’s house & we had 20 minutes alone with him, my first real conversation with him. He was very charming to me…”[40] He featured prominently in the Commission, battling with the Italians, but his role as liaison (in effect) with the Yugoslavs was equally important. On 30 May, Leeper, Crowe, Temperley and Nicolson “had half-a-dozen of the leading members of the Serb-Croat-Slovene Delegation to luncheon & put them in a good temper. We’ve trying times with them these days & have to see, soothe & reason with them all day long.”[41] Relations worsened, however, when, on 31 May, the Council blamed the Yugoslav (Serbian) army and Slovene irregulars for an outbreak of fighting with German-Austrians in the Basin.[42] The next affliction was the minorities clause in the Austrian treaty: Leeper found Brătianu and Trumbić “both rather tiresome” when they opposed this clause in the plenary session of 31 May.[43] The delegation’s 1 June letter “reserving our rights” in relation to the minorities clause associated them with the obstreperous Brătianu and provoked the Council’s brusque query as to whether it was proposed to sign the treaty and then not carry it out.[44]

Leeper’s account had it that “the Yugoslavs refused absolutely to sign the Austrian treaty if the present Klagenfurt plebiscite clauses stood” – but Nicolson was probably more accurate when he wrote that they “refused to be present at St. Germain” on 2 June for the presentation of the terms to Austria. At 11 p.m. on 1 June, Leeper and Nicolson visited the Yugoslav delegation and talked until 12.30 with Žolger and Vošnjak. The Slavs feared that a Basin-wide plebiscite “will go against them”, prompting Leeper and Nicolson to suggest the salami-slicing option of voting by communes, so that Yugoslavia “would get at least the southern portion”.[45] Leeper spoke with Cecil Hurst of the Drafting Committee early on 2 June, and Leeper, Nicolson and Hurst saw Lloyd George at 10 to press for voting by communes. They could not get to Wilson until the last moment, when he proved obdurate, but Clemenceau did what was needed when he tore the Klagenfurt page out of the treaty before it was presented to the Austrians.[46] Leeper described “a touch & go scene at St. Germain, the Yugoslav territorial clauses being simply abstracted from the treaty at the last moment & not given to the Austrians.” “Life’s really getting rather strenuous, though exciting.”[47]

This did not mean that Leeper and Nicolson succeeded in altering the nature of the plebiscite, for the decision now taken to avoid a single plebiscite did not follow their advice. In the Council on 2 June, Wilson opposed voting by commune because the Basin had “a geographic and economic unity, since it is completely surrounded by mountains”.[48] But Douglas Johnson told him that it was “impossible to accept as trustworthy” the idea that a majority of the Basin’s Slovenes preferred Austrian rule and, citing the merits (in terms of both geography and ethnography) of the Yugoslavs’ proposed line of partition, he challenged the idea that the Basin could not be divided.[49] Johnson posited two separate plebiscites, one in the predominantly Slovene south and one in the German north (including the city).[50] On 4 June, Wilson proposed that the Slovene part (Zone A) would vote separately(and first) on its future, and the more German Zone B would vote only if Zone A opted for Yugoslavia. Milenko Vesnić, not at all grateful, knew better than Johnson the true state of opinion and protested in vain that fifty years of Germanisation had conquered the national spirit of these Slovenes; they were “like birds which were too tame to fly”.[51]

At the end, Leeper was called in: Wilson and Lloyd George “took me into a corner & explained to me the decision taken”. He was instructed to “formulate a detailed plan” with the “other experts”.[52] On 5 June, he explained the new plebiscite(s) plan to Ivan Žolger, and soon he was back to contending with the Italians (who objected to Yugoslav administration, pending the plebiscite, of Zone A) in the Commission and enjoying their discomfiture (“Amusing passage of arms over Klagenfurt between Balfour & Sonnino”) as the Big Three outgunned them in the Council.[53] On 22 June, in attendance again at the Council, Leeper was “very pleased” that “the anguishing question of Klagenfurt was at last settled…”[54]

Over the following months, Leeper came to find the Yugoslavs quite bothersome as he staved off their many attempts to secure adjustments in the northern frontier. Their “absurd request” for Baja in the Bačka was turned down: “The Serb-Croat-Slovene Kingdom has already been assigned more of the Bačka than it is entitled to on strictly ethnic grounds.”[55] Yugoslav requests with regard to the Banat and Prekomurje (“The alterations now suggested are quite impossible geographically” – Leeper) were also rejected, but seven villages were added in the Baranja.[56] A mid-August proposal for a plebiscite at Mohács in the Baranja got short shrift from Leeper, who wondered if they should not see off the Yugoslavs by asking them “if they would accept one [a plebiscite] for the Bačka & Baranya as a whole”.[57] A second attempt to claim Baja was deemed “most unconvincing” and the demand for land near Szeged led Leeper to denounce “the immense & unjustifiable wrong” that would be done to the Hungarians, “the overwheming majority” there, for the sake of “these few hundreds of Serbs”.[58] An additional claim in the Baranja caused his comment that, “The Serb-Croat-Slovenes [sic] are greatly daring when it comes to the invention of statistics.”[59] In December, the Yugoslavs did receive an additional sliver of land north of the Drava at Gola. There was just time in January, before the Hungarians came to receive their treaty, for another unsuccessful attempt to claim Baja![60]

From August, before the treaties(St Germain and Trianon) were signed, the Yugoslavs were allowed to occupy the lands due to be awarded to them. Notably, on 1 August, the Allies gave Yugoslavia permission to occupy Prekomurje, ousting Bela Kun’s Reds; Leeper had called for this as “the most effective method of preventing the spread of Magyar Bolshevism”.[61] In October, the Yugoslavs were asked to evacuate all areas north of the new border and on 6 November the Council agreed to order them to withdraw from the last such territory, namely Pécs in the Baranja. Leeper, fingers in every pie, wrote that, “It seems to me both just & politic to insist that the Serbian evacuation of Pécs etc proceed pari passu with the Rumanian evacuation of Hungary. The Serbs will however offer great resistance to the abandonment of the coalfields.”[62] Leeper noted that the “largely socialist” workers of Pécs wanted the Yugoslavs to remain; although he doubted whether this “temporary disposition will long outweigh their Magyar racial feeling,” many of these workers regarded the occupation as protection from the post-Kun White Terror.[63] The Yugoslavs finally withdrew in August 1921, when the Treaty of Trianon came into effect, and the newly-proclaimed Baranja Republic, which sought a Yugoslav protectorate in vain, was invaded and suppressed by Horthy’s Hungarian army.

The loss of Klagenfurt was confirmed by the plebiscite held on 10 October 1920. Leeper (every pie!) had visited Klagenfurt before the vote and noted that “the country districts are largely Slovene though not necessarily all Yugoslav in sympathy”.[64] As shown in ‘Yugoslavia’, the plebiscite went against the Yugoslavs and the whole Basin stayed with Austria.

Fiuming experts

Leeper was more observer than active participant during the emergence of Fiume as the great point of difference between Italy and Yugoslavia. The March memorandum of the Yugoslavs, focused on the economic argument, was described by Leeper as “the best short statement of the Jugoslav claim to Fiume that we have received,” and he considered the furnished plan of the town sufficient “to show how right the Jugoslavs are in insisting that Fiume & Sušak are inseparable” – which was important, of course, in establishing the idea of a Slav majority.[65] Leeper also showed his colours when commenting on the encounter on 14 April between Andréa Ossoinack, the Fiume National Council’s so-called Plenipotentiary to the Peace Conference, and Wilson, considering it “satisfactory that Pres. Wilson took the occasion to answer the absurd arguments of this very suspect Italianised Croat”.[66]

When the American experts became alarmed by the possibility that Wilson would bow to Italian pressure and withhold Fiume from Yugoslavia, Leeper, no happier with his bosses, “expressed great fear and great disappointment both that Wilson was not standing more firmly and also that Lloyd George and Balfour were not stiffening him up more”.[67] However, Wilson publicly repudiated Italy’s claims on 23 April and his experts were “much elated at Wilson’s pronouncement on FIUME and Dalmatia”.[68] And most British comment was solidly behind Wilson. Harold Temperley considered Wilson’s statement “very noble & very determined” and Nicolson was “overjoyed”.[69] Leeper was jubilant but apprehensive:

What an extraordinary but not unexpected development! I’m glad of it & think Wilson did quite the right thing in appealing to his own & other sane public opinions. Orlando will now do the same & in the present inflamed state of feeling in Italy is sure of loud applause there. But what will happen then? Will Italy refuse to sign the peace with Germany or to enter the League of Nations? And what will be her position in that case? Well, one always knew the break wd come some time.[70]

He added that “the French think Wilson terribly maladroit. There’ll be trouble in Italy, sure. But wasn’t it ungetoutofthewayable?”[71] Robert Vansittart’s later verdict showed more appreciation of the adverse reaction: “Over the head of an unwise Italian government he appealed unwisely to an unwise Italian people, who became more unwise than ever.”[72]

The British – Leeper, Temperley and Nicolson, aided by Seton-Watson – prepared a plan which gave the Italians a little more land in Istria and set out “a series of graded offers” involving the islands of Lissa (Vis) and Lussin (Lošinj), “sov[ereign]ty in Albania, or concessions in Asia Minor”. “To-day,” Leeper wrote on 26 April, “we’ve been working out an Italo-Jugoslav compromise.”[73] This work continued into May, when Leeper’s frustration with the Italians was evident:

There’s lots still to do here with this ever-present Italo-Yugoslav controversy & the Italians behaving as criminal maniacs.[74]

Have been so busy with Fiume & the whole Italian question. Such Machiavellini as they are. I hope we’ll be very firm. The battle is fairly joined…[75]

I enclose … two copies of our memo. which has been “seen” by Mr. Balfour: whether it will be adopted at all I don’t know – one is quite vague as to what terms Ll. G. proposes to make with the Italians.[76]

Wilson referred in the Council to “some suggestions” which, he believed, had “emanated from the British Delegation. It so happened that their line, drawn quite independently, corresponded very closely to the line drawn by the American experts.”[77] Leeper was a close working partner of the American experts and it is likely that his memorandum was passed by them to Wilson.[78]

Leeper also worked on British and French recognition of Yugoslavia: “A busy day ’cause we are about I hope to recognize the Yugoslavs & I had to betake me to the Quai d’Orsay to sound & specify French intentions. Franco-British co-operation, what?”[79] The leaders cooperated, in fact, to obstruct the measure, with Balfour, Lloyd George and Clemenceau unwilling “to do anything to increase the danger of an explosion in Italy” (Lloyd George).[80] In the end, it was decided that by accepting the Yugoslav credentials at the Peace Conference, “we are by that very fact recognizing the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, without needing to make any formal statement” (Clemenceau).[81] The draft treaty presented to the Germans on 7 May listed the country as “Serbie-Croatie-Slavonie”, causing an annoyed Leeper to present a short historical lecture on the difference between Slovenia and Slavonia and to advise use of the full and correct name, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes.[82]

Despite the profusion of Adriatic plans during May 1919, notably those of Douglas Johnson, Colonel House and André Tardieu, agreement could not be reached on either Fiume or Istria. Orlando’s government, castigated by disappointed nationalists, fell on 19 June. Orlando and Sonnino would not be missed: Leeper reflected on “how traitorous the Italian politicians have been to us” and Nicolson declared that Italian diplomacy had been “stupid and dishonest”.[83]

Failure

Leeper had little to do with the negotiations that recommenced in July. He apparently continued in his customary role as a link with the Yugoslavs, who were confined largely to waiting anxiously on the sidelines: “Smodlaka came in the morning: Adriatic negotiations reached another deadlock over the “buffer state” idea.”[84] At this stage, he was not optimistic and, on 20 August, his brother reported Leeper’s concern that Nicolson (briefly involved again) and his colleagues were “not making much headway with the Adriatic question, though a week ago he was more hopeful. He says he is sick to death of it, as it goes on week after week and they never seem to get to the end of it.”[85] On the 29th, however, the Italians accepted Wilson’s line in Istria and gave up most of Dalmatia. A settlement seemed within reach, Leeper writing next day that, “The Adriatic question is at last nearer a fair solution than I could have hoped: but there’s many a slip ___!”[86] He subsequently described the 29 August proposal as “a great stage on the part of the Italian Government towards a moderate and reasonable point of view… The only seriously contentious question left in existence by the Italian note was that of Fiume.”[87] This appeared in a long account, dated 11 October, of the negotiations; it was the work of an unnamed member of the British delegation, but Leeper’s diary indicates that he was responsible.[88]

After d’Annunzio’s seizure of Fiume on 12 September 1919, Leeper was one of those who feared that, “The danger of a clash between Italian & Yugoslav troops appears considerable. Unless D’Annunzio is forced to evacuate Fiume, the Yugoslavs will certainly imitate his example & seize what they want by violent means.”[89] This did not materialise, but the nationalist excitement in Italy forced the government into a more hardline position. In October, Tittoni demanded an independent Fiume (under Italian control) and the coastal strip between the Italian part of Istria and the city of Fiume. The Americans rejected this scheme and Leeper was equally hostile: “What the Italian Govt. apparently ask us to do is agree to a totally unjust & unworkable arrangement in order to assuage the mutinous spirit of the Italian army & navy.”[90]

It was not until December that Leeper, preoccupied as he was with the problem of Romania’s occupation of Hungary, made his first significant intervention in the Adriatic question. Lloyd George’s end-of-October dalliance with Prime Minister Nitti (see ‘Yugoslavia’) prompted the Americans to send Isaiah Bowman to explain Wilson’s in-no-circumstances stance to Leeper on 13 November: “in no circumstances whatsoever” would Wilson agree to “the contiguity of the territories of Italy and Fiume” (the coastal strip); “President Wilson’s line [in Istria] could not in any circumstances be placed further east”; as for the future of Fiume, “In no circumstances could the city of Fiume be excluded from the [projected] buffer state and accorded complete independence.” When Bowman told Leeper that he was preparing a memorandum stating America’s “last word” on the Adriatic question, Leeper suggested that it should come from all of the Big Three, to end Italian hopes that they might exploit differences between Wilson and his British and French partners.[91] Crowe (Balfour’s successor as head of delegation), Frank Polk of the United States and Clemenceau approved the idea on 28 November.

Next day, Leeper was “all the morning busy dictating draft for joint Adriatic communication” – “I wrote the first draft,” he told his stepmother – which “provisional draft” Crowe sent to London on 2 December.[92] Given that this draft was almost identical to the final version, Leeper must be regarded as the primary author of the joint memorandum. Nicolson subsequently gave him the full credit: “It was he who drafted and pushed through the joint Clemenceau-Polk-Crowe memorandum of December 9th, which at least represented the elements of the best solution which our ‘damnosa hereditas’ could offer. I really feel that you [Seton-Watson] should realise how entirely the acceptance of that memorandum was due to Leeper’s own prestige in Paris. No one else could have got it through.”[93] This is not to say he made the policy, for the paper merely presented and explained American policy: it saw Britain and France coming into line with the views expressed in Lansing’s correspondence with the Italians, rejecting the coastal strip to Fiume and the idea of a separate city state and sustaining the Wilson Line in eastern Istria.[94]

Leeper then had a major role in the last great effort at finding a solution, in London in January 1920, when Lloyd George led the way towards conciliating the Italians and ditching the Yugoslavs, who were told that if they blocked a compromise Italy would proceed to apply the terms of the Treaty of London. Leeper “helped to finish [the] final draft” of a new plan and was then called in by Lloyd George “to help to explain maps to Clemenceau” on 9 January.[95] And he was present when the Premiers of Britain, France and Italy (the Council of Three) made the key decisions on 12, 13 and 14 January:

Very busy all day, first at Claridge’s, then at the Council of 3. In the morning Trumbić finished his statement.[96] After lunch there was a 3 hours discussion. Nitti gave up his demands for Cherso, Lagosta, Zara, demilitarisation of Dalmatia & a buffer state, & was conceded Fiume town & a coastal strip connecting it with Italy. I [Leeper] supplied Ll. G. with much material which he used very skilfully. Decided to talk to Trumbić to-morrow.[97]

Went to Claridge’s at 11. The P.M. received Nitti (in one room) & Trumbić in another & passed from one to the other negotiating. I was only called in after Nitti had gone & explanations were being given to Trumbić. The P.M.’s proposals – more or less accepted by Nitti – include (1) Italian sovereignty over town of Fiume, (2) Port of Fiume-Sušak to the League of Nations, (3) road but not railway connection between Fiume & Italy, (4) Senosecchia area to Italy, (5) [the islands of] Lussin, Pelagosa, Lissa & Lagosta to Italy, (6) No demilitarisation except Sebenico, (7) N. Albania to Yugoslavia, (8) Zara Free City.

I dashed off to lunch… Back to Claridges’s to finish drafting the proposals & making a map. Then at Quai d’Orsay. Interesting discussion. Clemenceau agreed to Ll. G.’s proposals but tog[ether] they persuaded Nitti to give up Lagosta & the demilitarisation of Sebenico… Then came Pašić & Trumbić. Meanwhile I drafted the new scheme. Clemenceau spoke exceedingly well agreeing with the justice of the S.C.S. demands but urging on them the political necessity of signing now.[98]

To Claridge’s at 3.30 & saw S.C.S. reply. A complete ‘non possumus’ [we can not] on Fiume, islands, everything. Then to Quai d’Orsay. Clemenceau persuaded Nitti to concede Fiume to be Free City, not Italian. Then Trumbić & Pašić came in. Clem. urged them very strongly to accept: otherwise no course but Pact of London. Trumbić at first very determined, afterwards a little shaken. Asked for 2 days to refer to Belgrade. I was busy dashing from room to room. I urged Trumbić very strongly to accept [the] new terms.[99]

So, according to Leeper’s diary entry for 13 January, Lloyd George and Clemenceau initially proposed to give Fiume to Italy! D’Annunzio’s “impresa” reverberated even in Downing Street. Italy did renounce Fiume at the last moment (on 14 January), so that the “January Compromise” made Fiume (and Zara) independent “with the right to choose its own diplomatic representation” (which was expected to be Italy) and gave the coastal strip and almost all of Istria to Italy.[100] Beside Lloyd George, who was the driving force in these negotiations, stood a slightly dazzled Allen Leeper:

I’m off to Paris to-morrow in the special train with Lloyd George & Curzon. I’ve had a very interesting, though harassing day, seeing them both a lot in turn. Fiume![101]

I’ve been having a frightfully busy & anxious, but very interesting time. The Adriatic question has been the one chiefly discussed & the negotiations have been very arduous. It’s been very interesting for me being so much in it all as I’ve been the only person (except Hankey) present in attendance on Ll. G. at all the Council of Three’s meetings on the subject & so have had a fair say in things. Don’t repeat all this for it sounds so swanky: I only tell you for your own information. It is not an ideal settlement proposed but far better than at one time I hoped & I’ve strongly urged the Yugoslavs to sign. We shall know definitely in a few days so that it’s no use forecasting now.

I’ve met a good many great ones lately & had talks with Clemenceau, Nitti & others…[102]

Leeper also continued to be the principal liaison with the Yugoslavs; he “urged Trumbić very strongly” to accept the so-called Compromise and on 19 January he “saw Pašić [head of delegation]. Urged on him [the] necessity of his Govt. signing [the] Adriatic agreement at once.”[103] He pressed Lupis-Vukić, one of the Yugoslav advisers, “to persuade his delegation to sign the Adriatic arrangement in order to destroy the Treaty of London” – cleverly spinning the threat as an opportunity. Lupis-Vukić, denouncing the whole project to Seton-Watson, blamed Lloyd George and the Italians (“So – there we are: D’Annunzio, Nitti, Sonnino, they are all alike!”).[104] But he was also hurt by the stance taken by a presumed friend: Leeper “invited me twice to him – entreated, beseeched, threatened, tried all to impress me with the necessity of accepting the project of the Big Three. He said, if we decline, we will loose favors [sic]of England and France in everything; if we do [accept], we will earn their support and gratitude for having helped to annull [sic] the Pact of London.”[105] Seton-Watson duly faulted Leeper’s “urging the Jugoslavs to give in to this cynical & disgraceful ultimatum”.[106] Nicolson gave an idea of the strains involved when a junior official is exposed to the abrasiveness of politics: “We are going through a dreadful period here. Poor Leeper has aged ten years in the last four days. If this cynical & flippant recklessness is a foretaste of the new diplomacy I almost (though not quite) regret the old.” He found Leeper “somewhat distressed” by Seton-Watson’s letter; “I must say I think you [Seton-Watson] have been somewhat unjust to him.”[107] Leeper’s reply to Seton-Watson shows him slightly troubled but ultimately resolute and unapologetic:

[W]hat is the position? This has been done. There are two alternatives:

- The Yugoslavs – as I have advised them – might sign. The Treaty of London is ipso facto & for ever destroyed. They obtain almost all the territory they desire except the ‘coastal strip’…

- They may refuse to sign. Then the Treaty of London comes into force… [Lloyd George and Clemenceau will] simply say, ‘Then we wash our hands of the whole thing; the Treaty of London exists; you Yugoslavs & Italy may make what arrangements you like.’

That’s the fact. I don’t approve: I register the fact. It’s on the basis of this deplorable fact that I’ve given advice to the Yugoslavs… I think Trumbić knows I’m doing my best for them – without much effect, I admit.[108]

The villain of the piece was Lloyd George, so careless with “other people’s property” (Nicolson), and Leeper had tried to make his leader’s efforts “as innocuous as possible”.[109]

On 28 January, the Yugoslavs rejected the January Compromise. Leeper, continuing to advise and cajole, hinted at the Yugoslavs’ hope that Wilson would save them:

[T]alked for an hour with Karović [Pašić’s private secretary] & then an hour with Trumbić. I again repeated every argument in favour of signing. It had no full effect however, especially as their instructions from Belgrade were stringent. Trumbić read me their formal reply (which he went on to the Quai d’Orsay to deliver to Paléologue at 8 o’clock). At my advice he cut out the last two sentences hinting at a superior American judgment. The reply was dignified but not as skilful as I shd have liked. I again suggested even provisional acceptance with ultimate ratification by League of Nations. This rather impressed him. We talked exceedingly amicably.[110]

Leeper did not give up and on 11 February he “saw Lord Curzon & explained that Trumbić was in London & wd be willing to accept a settlement giving Fiume in full sovranty [sic] to Italy (minus the port), if the Italians accepted the “Wilson line” as frontier.” He wrote a short paper proposing such a settlement.[111]

Wilson’s excoriating denunciation of the Compromise on 10 February 1920 ended the whole endeavour and the peacemakers simply gave up. It would be left to Italy and Yugoslavia to make a separate agreement, outside (and after) the Conference. The negotiations between two states of very unequal strength reached a predictable conclusion on 12 November 1920, when the Treaty of Rapallo saw Yugoslavia denied Fiume, the coastal strip, all of Istria, Zara in Dalmatia and four Dalmatian islands, and Mussolini completed the job when Italy took over Fiume, until then nominally independent, in 1924. Leeper called Rapallo a “complete capitulation” and Wilson, about to leave office, wrote that Italy was creating “a new Alsace-Lorraine” which was “sure to contain the seeds of another European war” – and, if it did lead to war, “personally I shall hope that Italy will get the stuffing licked out of her.”[112]

War did not ensue and other, wider ambitions brought down Italy (and cost her Fiume and Trieste). Nevertheless, the Adriatic dispute was one of the great failures of the Peace Conference, which did not manage to make any sort of settlement. Intransigent Wilson and unprincipled Lloyd George were probably equally blameworthy, even allowing for the fact that the Italians and Yugoslavs were irreconcilable. Leeper and other delegates explored many possible solutions but did not find one that was acceptable to both parties. When an ally was in dispute with an enemy, the answer was to favour the ally. When two allies were in dispute, the peacemakers, at least in this case, had no answer.

[1] The Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was the country’s formal name, but the words “Yugoslav” and “Yugoslavia” were used on almost every occasion during the deliberations of 1919.

[2] Foreign Office Papers, FO 371/4355, 24, South-Eastern Europe and the Balkans, December 1918. FO 608/15, 387, The Question of Trieste, notes by Nicolson and Leeper, 20, 21 January 1919.

[3] Ibid.,, 411, Future of Fiume, note by Leeper, 25 January 1919; FO 608/35, 165, 170, 183, 192, notes by Leeper, 8, 15, 17 March, 19 April 1919; FO 608/28, 37, note by Leeper, 31 March 1919.

[4] Papers of Allen Leeper (LEEP), 3/8, Leeper to Rex Leeper, 30 January 1919.

[5] FO 608/41, 432, note by Leeper, 19 February 1919. FRUS, IV, 49-53, Council of Ten, 18 February 1919.

[6] FO 608/42, 343, Extract of a report of Korošec’s newspaper interview, 18 January 1919, with note by Leeper, 6 March 1919.

[7] Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States: The Paris Peace Conference 1919 (FRUS), IV, 54-55, Council of Ten, 18 February 1919.

[8] Leeper called it “a very poor compromise but perhaps the only one”. Papers of Allen Leeper (LEEP), 3/8, Leeper to Rex Leeper, 19 February 1919.

[9] FRUS, III, 489, Council of Ten, 12 January 1919.

[10] FO 608/34, 1, Memorial of Milan Koracevic, 13 February 1919, with note by Leeper, 26 February 1919.

[11] FO 608/41, 458, Notes on a Visit to Syrmia by Roland Bryce, February 1919, with note by Leeper, 25 March 1919.

[12] Ibid., 463, note by Leeper, 28 March 1919.

[13] Ibid., 537, note by Leeper, 22 May 1919.

[14] Ibid., 432, note by Leeper, 19 February 1919. Commission des Affaires Roumaines et Yougo-Slaves, FO 374/9, Procès-Verbal No. 7, 65-66, 25 February 1919; No. 9, 77-8, 81, 2 March 1919; No. 16, 142, 13 March 1919.

[15] FO 608/41, 453, note by Leeper, 22 March 1919, with Smodlaka’s Economic Reasons why Baranja should be united with the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes.

[16] Commission des Affaires Roumaines et Yougo-Slaves, FO 374/9, Procès-Verbal No. 17, 163-64, 18 March 1919; Report, 227. Medjumurje had 82,886 Slavs in a population of 90,387. Ibid., Procès-Verbal No. 20 (Annexes), 235, Tableaux Statistiques.

[17] Ibid., Procès-Verbal No. 15, 135-36, 138-39, 11 March 1919; No. 16, 149, 13 March 1919; No. 17, 163-64, 18 March 1919, Report; 227-28, Report on the Frontiers of Yugoslavia, 6 April 1919: Frontier between Yugoslavia and Austria; No. 26, 305, 20 May 1919. T. G. Otte, ed., An Historian in Peace and War: The Diaries of Harold Temperley (Farnham and Burlington, 2014), 421, 20 May 1919. FO 608/41, 530, Leeper to Crowe, 16 May 1919.

[18] Commission des Affaires Roumaines et Yougo-Slaves, FO 374/9, Procès-Verbal No. 9, 79-80, 2 March 1919; No. 17, 165, 18 March 1919; 228-29, Report on the Frontiers of Yugoslavia, 6 April 1919.

[19] Papers of Allen Leeper (LEEP), 3/8, Leeper to Rex Leeper, 8 March 1919.

[20] Ibid., 3/8, Leeper to Rex Leeper, 13 March 1919.

[21] Ibid., 3/8, Leeper to Rex Leeper, 8 May 1919.

[22] Ibid., 3/8, Leeper to Rex Leeper, 10 May 1919. Commission des Affaires Roumaines et Yougo-Slaves, FO 374/9, Procès-Verbal No. 21, 264-69, 9 May 1919.

[23] Otte, Diaries of Harold Temperley, 411-13, 10 May 1919. Papers of Allen Leeper (LEEP), 3/8, Leeper to Rex Leeper, 10 May 1919.

[24] Ibid.. Nicolson, Peacemaking 1919, 331, Diary, 10 May 1919.

[25] Otte, Diaries of Harold Temperley, 413-14, 10 May 1919.

[26] Papers of Allen Leeper (LEEP), 3/8, Leeper to Rex Leeper, 10, 12 May 1919. FRUS, IV, 697-98, Council of Foreign Ministers, 10 May 1919 (Balfour).

[27] Papers of Allen Leeper (LEEP), 3/8, Leeper to Rex Leeper, 10 May 1919.

[28] Most subsequent negotiations gave Assling to Yugoslavia and this was the outcome at Rapallo in 1920.

[29] Ibid., 3/8, Leeper to Rex Leeper, 12 May 1919. Temperley was less modest in his assessment of his own influence with Lloyd George and service to the Yugoslav cause. Otte, Diaries of Harold Temperley, 414, 10, 11 May 1919.

[30] Ibid., 419-20, 18 May 1919. FO 608/41, 528, Leeper to Crowe, 15 May 1919.

[31] Ibid., 530, Leeper to Crowe, 16 May 1919.

[32] Papers of Allen Leeper (LEEP), 1/2, Leeper’s Diary, 40, 16, 17 May 1919; ibid., 3/8, Leeper to Rex Leeper, 16, 19 May 1919.

[33] Ibid., 3/8, Leeper to Rex Leeper, 19 May 1919. Commission des Affaires Roumaines et Yougo-Slaves, FO 374/9, Procès-Verbal No. 24, 288-91, 19 May 1919.

[34] Otte, Diaries of Harold Temperley, 424-25, 27 May 1919.

[35] Papers of Allen Leeper (LEEP), 3/8, Leeper to Rex Leeper, 20 May 1919. Ibid., 1/2, Leeper’s Diary, 41, 20 May 1919: “Agreement over Prekmurje but Americans objected to Klagenfurt plan.”

[36] Charles Seymour, Letters from the Paris Peace Conference by Charles Seymour , ed. by Harold B. Whiteman, Jr. (New Haven and London, 1965), 240, 246, Seymour to Mr and Mrs Thomas Watkins, 21, 28 May 1919.

[37] Papers of Allen Leeper (LEEP), 3/8, Leeper to Rex Leeper, 28 May 1919. Temperley’s account is fuller and more colourful. Otte, Diaries of Harold Temperley, 424-25, 27 May 1919.

[38] Papers of Allen Leeper (LEEP), 3/8, Leeper to Rex Leeper, 29 May 1919; ibid., 1/2, Leeper’s Diary, 40, 29 May 1919. Letters from Charles Seymour, 250, Seymour to Mr and Mrs Thomas Watkins, 31 May 1919. Nicolson, Peacemaking 1919, 351, Diary, 29 May 1919.

[39] Papers of Allen Leeper (LEEP), 3/8, Leeper to Rex Leeper, 29 May 1919. The not-so-secret story of the negotiations in May 1919 was told in a Laibach newspaper on 23 July, which story was endorsed by Leeper as a “fairly accurate & quite amusing history of part of the Klagenfurt controversy”. FO 608/43, 430, The Green Line in Carinthia, with note by Leeper, 13 August 1919.

[40] Papers of Allen Leeper (LEEP), 1/2, Leeper’s Diary, 44, 29 May 1919.

[41] Ibid., 3/9, Leeper to Mary Elizabeth Leeper, 7 June 1919; ibid., 3/8, Leeper to Rex Leeper, 1 June 1919; ibid., 1/2, Leeper’s Diary, 44, 30 May 1919. See also Nicolson, Peacemaking 1919, 352, Diary, 30 May 1919.

[42] FRUS, VI, 115, 134-35, Council of Four, 30, 31 May 1919. Paul Mantoux, The Deliberations of the Council of Four (Princeton, 1992), II, 254-55, 30 May 1919.

[43] Papers of Allen Leeper (LEEP), 3/9, Leeper to Alexander Leeper, 7 June 1919; ibid., 3/8, Leeper to Rex Leeper, 1 June 1919. See also Papers of Sir James and Agnes Headlam-Morley, Account 727/1, Political Diary, 1 June 1919. FRUS, III, 403-4, Plenary Session of the Peace Conference, 31 May 1919.

[44] FRUS, VI, 160, 163-64, Council of Four, 3 June 1919.

[45] Papers of Allen Leeper (LEEP), 3/8, Leeper to Rex Leeper, 2 June 1919. Nicolson, Peacemaking 1919, 355-56, Diary, 1 June 1919.

[46] Ibid., 356-57, Diary, 2 June 1919.

[47] Papers of Allen Leeper (LEEP), 3/8, Leeper to Rex Leeper, 2 June 1919. Ibid., 1/2, Leeper’s Diary, 45, 2 June 1919.

[48] FRUS, VI, 138, Council of Four, 2 June 1919. Mantoux, Deliberations of the Council of Four, II, 268, 2 June 1919. See also Arthur S. Link, ed., The Papers of Woodrow Wilson (Princeton, 1989), Volume 60, 22, Wilson to Scott, 2 June 1919.

[49] Ibid., 34-38, Johnson to Wilson, 2 June 1919.

[50] Ibid., 121-22, Johnson to Wilson, 4 June 1919.

[51] FRUS, VI, 173-80, Council of Four, 4 June 1919. Mantoux, Deliberations of the Council of Four, II, 298-304, 4 June 1919. Vesnić had been called in to address the Council.

[52] Papers of Allen Leeper (LEEP), 3/8, Leeper to Rex Leeper, 5 June 1919; ibid., 1/2, Leeper’s Diary, 45, 4 June 1919. FRUS, VI, 180, Council of Four, 4 June 1919.

[53] Papers of Allen Leeper (LEEP), 1/2, Leeper’s Diary, 46, 50, 5, 19 June 1919; ibid., 3/8, Leeper to Rex Leeper, 6, 19 June 1919.

[54] Ibid., 3/8, Leeper to Rex Leeper, 22 June 1919.

[55] FO 608/41, 577, note by Leeper, 3 July 1919.

[56] Ibid., 587, 589, notes by Leeper, 9, 11 July 1919. FRUS, VII, 75-6, 454-55, 468-74, Heads of Delegations, 9 July, 1 August 1919.

[57] FO 608/41, 614, note by Leeper, 21 August 1919. See also Otte, Diaries of Harold Temperley, 451, 6 August 1919.

[58] FO 608/42, 472, 476, notes by Leeper, 1 September 1919.

[59] Ibid., 127, note by Leeper, 28 October 1919. For Leeper’s and Crowe’s rejection of other Yugoslav claims against Hungary, see ibid., 1, 4, 93, 105, notes by Leeper and Crowe, 22, 29 August, 6, 7, 8 October 1919; ibid., 94, Leeper to Crowe, 14 October 1919.

[60] Heads of Delegations, CAB 29/77, 374, 6 January 1920 (also in FRUS, IX, 811-12). Andrej Mitrović in Dimitrije Djordjević, ed., The Creation of Yugoslavia 1914-1918 (Santa Barbara and Oxford, 1980), 211-12.

[61] FO 608/41, 580, note by Leeper, 7 July 1919; ibid., 581, Leeper to Crowe, 18 July 1919.

[62] FO 608/15, 302, note by Leeper, 31 October 1919.

[63] FO 371/3519, 508, note by Leeper, 4 March 1920.

[64] Papers of Allen Leeper (LEEP), 3/11, Leeper to Alexander Leeper, 20 August 1920.

[65] FO 608/8, 545, 554, The Future of the Port of Fiume, with note by Leeper, 31 March 1919.

[66] FO 608/35, 60, Report of the Conference between Wilson and Ossoinack, 14 April 1919, with note by Leeper, 14 May 1919. Leeper previously commented that, “In spite of his misspelt Croat name, he [Ossoinack] is a thoroughly sound Italian Jingo.” Ibid., 28, note by Leeper, 17 March 1919.

[67] Letters from Charles Seymour, 204, Seymour to Mr and Mrs Thomas Watkins, 16 April 1919. Leeper and Nicolson dined with Seymour and Day (and their wives) and found them “both very good types of American”. Papers of Allen Leeper (LEEP), 3/8, Leeper to Rex Leeper, 18 April 1919.

[68] Temperley wrote this after dining with Seymour, Day and others. Otte, Diaries of Harold Temperley, 402, 23 April 1919. See also James T. Shotwell, At the Paris Peace Conference (New York, 1937), 293, Shotwell’s diary, 23 April 1919. Letters from Charles Seymour, 209-11, Seymour to Mr and Mrs Thomas Watkins, 25 April 1919.

[69] Otte, Diaries of Harold Temperley, 402-3, 24 April 1919. Nicolson, Peacekeeping 1919, 317, Diary, 27 April 1919.

[70] Papers of Allen Leeper (LEEP), 3/8, Leeper to Rex Leeper, 24 April 1919.

[71] Ibid., 3/8, Leeper to Rex Leeper, 28 April 1919.

[72] Lord Vansittart, The Mist Procession: The Autobiography of Lord Vansittart (London, 1958), 217. Nicolson later wrote that “by then the agitation in Italy had reached such a point that this appeal did far more harm than good.” [Nicolson], ‘The Peace Conference and the Adriatic Question’, Edinburgh Review, Volume 231, No. 472 (April 1920), 225.

[73] Otte, Diaries of Harold Temperley, 404, 26 April 1919. Papers of Allen Leeper (LEEP), 3/8, Leeper to Rex Leeper, 26 April 1919. See also Nicolson, Peacemaking 1919, 315, Diary, 25 April 1919.

[74] Papers of Allen Leeper (LEEP), 3/9, Leeper to Alexander Leeper, 4 May 1919.

[75] Ibid., 3/8, Leeper to Rex Leeper, 6 May 1919.

[76] Ibid., 3/8, Leeper to Rex Leeper, 7 May 1919.

[77] Mantoux, Deliberations of the Council of Four, II, 50, 13 May 1919. FRUS, V, 579, Council of Four, 13 May 1919.

[78] Hankey did not name individuals but wrote that, “This is only one example of a very important effort by American and British experts to get together spontaneously to help their chiefs.” Lord Hankey, The Supreme Control at the Paris Peace Conference 1919 (London, 1963), 165.

[79] Papers of Allen Leeper (LEEP), 3/8, Leeper to Rex Leeper, 28 April 1919.

[80] Mantoux, Deliberations of the Council of Four, I, 393-94, 28 April 1919. Temperley blamed the French. Otte, Diaries of Harold Temperley, 405, 29 April 1919.

[81] Mantoux, Deliberations of the Council of Four, I, 410-11, 29 April 1919. FRUS, V, 338, Council of Four, 29 April 1919. Otte, Diaries of Harold Temperley, 405, 30 April 1919. FO 608/42, 318, Hankey to Dutasta, 29 April 1919, “no special public declaration”.

[82] Ibid., 321, note by Leeper, 8 May 1919. Crowe agreed but thought it “a national calamity for a new state to be burdened with such an elephantine designation”. Ibid., note by Crowe, 9 May 1919.

[83] Papers of Allen Leeper (LEEP), 3/8, Allen Leeper to Rex Leeper, 20 June 1919. Nicolson, Peacemaking 1919, 365, Diary, 27 June 1919.

[84] Papers of Allen Leeper (LEEP), 1/2, Leeper’s Diary, 67, 19 August 1919.

[85] Seton-Watson Collection, SEW/17/14/5, Rex Leeper to Seton-Watson, 20 August 1919.

[86] Ibid., Leeper to Seton-Watson, 30 August 1919.

[87] FO 608/41, 315, British Delegation Minute (Leeper), 11 October 1919.

[88] Papers of Allen Leeper (LEEP), 1/2, Leeper’s Diary, 82, 11 October 1919.

[89] FO 608/41, 157, note by Leeper, 30 September 1919.

[90] Ibid., 365, 369, notes by Leeper, 29 (2) October 1919.

[91] FO 608/28, 227, 230, Leeper’s Memorandum on the American Attitude to Italian Claims in the Adriatic, 14 November 1919.

[92] Papers of Allen Leeper (LEEP), 1/2, Leeper’s Diary, 28, 29 November, 3 December 1919; ibid., 3/9, Allen Leeper to Mary Elizabeth Leeper, 7 December 1919. E.L. Woodward and Rohan Butler, eds., Documents on British Foreign Policy 1919-1939 (London, 1956), First Series, Vol. IV, 214-24, Crowe to Curzon, 29 November, 2 December 1919, enclosing Draft Memorandum.

[93] Seton-Watson Collection, SEW/17/19/1, Nicolson to Seton-Watson, 4 February 1920. Leeper claimed the authorship in a late-January letter to Seton-Watson – “our (‘my’!) Memorandum of 9th Dec.” – and the latter’s biographers were emphatic: “The Note was drafted by Allen Leeper.” Seton-Watson Collection, SEW/14/5, Leeper to Seton-Watson, 31 January 1920. Hugh and Christopher Seton-Watson, The Making of a New Europe, 397, 413n24.

[94] Except that Albona could go to Italy. Link, Papers of Woodrow Wilson, Volume 64, 168-78. Correspondence relating to the Adriatic Question (Parliamentary Paper, London, 1920), 3-9.

[95] Papers of Allen Leeper (LEEP), 1/3, Leeper’s Diary, 7, 9 January 1920; ibid., 3/11, Leeper to Alexander Leeper, 7 January 1920.

[96] This refers to the review of the Adriatic question that Trumbić was asked to give the Council on 10 January. DBFP, First Series, II, 803-22, Notes of Meetings of 10, 12 January 1920. Ivo J. Lederer, Yugoslavia at the Paris Peace Conference: A Study in Frontiermaking (New Haven and London, 1963), 263-64.

[97] Papers of Allen Leeper (LEEP), 1/3, Leeper’s Diary, 12 January 1920.

[98] Ibid., Leeper’s Diary, 13 January 1920.

[99] Ibid., Leeper’s Diary, 14 January 1920. DBFP, First Series, II, 803-32, 856-65, 867-83, Notes of Meetings of 10, 12, 13, 14 January 1920. See also Seton-Watson Collection, SEW/17/15/2, Lupis-Vukić to Seton-Watson, 14 January 1920.

[100] Correspondence relating to the Adriatic Question, 18, Revised Proposals of 14 January 1920.

[101] Papers of Allen Leeper (LEEP), 3/11, Leeper to Alexander Leeper, 7 January 1920.

[102] Ibid., 3/11, Leeper to Alexander Leeper, 17 January 1920.

[103] Ibid., 1/3, Leeper’s Diary, 19 January 1920.

[104] Seton-Watson Collection, SEW/17/15/2, Lupis-Vukić to Seton-Watson, 14, 21 January 1920.

[105] Ibid., Lupis-Vukić to Seton-Watson, 25 January 1920. This was the revised “Big Three”, of course, with Italy (Nitti) in place of America (Wilson).

[106] Ibid., SEW/17/14/5, Seton-Watson to Leeper, 28 January 1920.

[107] Ibid., SEW/17/19/1, Nicolson to Seton-Watson, 12 January, 4 February 1920.

[108] Ibid., SEW/17/14/5, Leeper to Seton-Watson, 31 January 1920.

[109] Ibid., SEW/17/19/1, Nicolson to Seton-Watson, 4 February 1920.

[110] Correspondence relating to the Adriatic Question, 22-23. Papers of Allen Leeper (LEEP), 1/3, Leeper’s Diary, 28 January 1920. Maurice Paléologue was the General Secretary of the French Foreign Office.

[111] Ibid., 3/11, Leeper to Mary Elizabeth Leeper, 6 February 1920; ibid., 1/3, Leeper’s Diary, 8, 11 February 1920. DBFP, First Series, XII, 132, Memorandum by Leeper on the Adriatic Question, 13 February 1920.

[112] Papers of Allen Leeper (LEEP), 1/3, Leeper’s Diary, 15 November 1920. Link, The Papers of Woodrow Wilson, Volume 66, 367, Wilson to Colby, 15 November 1920. Wilson’s letter is quoted in full in ‘Yugoslavia’.