Bulgaria, refighting the previous, lost war, made the irrecoverable mistake of choosing the wrong side in the First World War, when she sought to gain revenge on (and take territories from) the neighbours who had defeated her in the Second Balkan War of 1913. These countries – Serbia, Romania and Greece – were in the camp of the eventually victorious Alliance and their leaders went to Paris in 1919 to demand a peace that would both expand their frontiers and ensure the eclipse of Bulgaria as a regional power. The British and French regarded Bulgaria’s aggression in 1915-16 as selfish opportunism.[1] They were willing to give the victims, their allies, almost everything they wanted and to face down American opposition with arguments in which there was one dominant idea: these people are our friends and those are our enemies.

In September 1918, British, French, Serbian and Greek forces advanced into Bulgaria from the south and forced the country’s surrender in the armistice signed at Salonica on 29 September 1918. The Allied politicians arrived in Paris in December 1918 and January 1919 to begin work on the European peace settlement. As with all of the defeated nations, however, the Bulgarians were not allowed to go to Paris to negotiate a peace treaty. They were finally permitted to travel there in July 1919 and, even then, their treaty was not ready so that the delegates “dangled till mid-September without an Article to chew”.[2] Required to wait longer than any other defeated country’s representatives, they stayed out at Neuilly-sur-Seine and, “caged lions”, were forbidden to receive visitors or to go out unless accompanied by the French police.[3]

The draft treaty (“Peace Conditions”) was presented to the Bulgarians on 19 September 1919. Their response, the Bulgarian Observations of 24 October, prompted only small changes and the Allies bluntly reminded them that “the support of the country” had been given to “a Government which satisfied its territorial cravings by undertaking a policy of conquest”.[4]

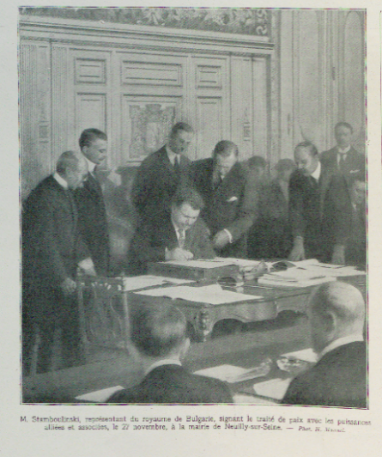

The delegation was given 10 days to agree to sign the treaty – failure would mean that the armistice would be considered at an end – and duly informed the Supreme Council on 13 November that it “would sign but yields to force”.[5] On 27 November 1919, Britain’s Allen Leeper and other Allied representatives “motored out to Neuilly to be present at the signature of the Bulgarian Peace Treaty at 10.30: interesting but quiet & short (½ hr)”.[6] Bulgaria’s Prime Minister, Aleksandŭr Stamboliĭski – “scared and wall-eyed” and looking like “the office boy [who] had been called in for a conference with the board of directors” – signed the treaty in Neuilly town hall.[7]

The territorial settlement

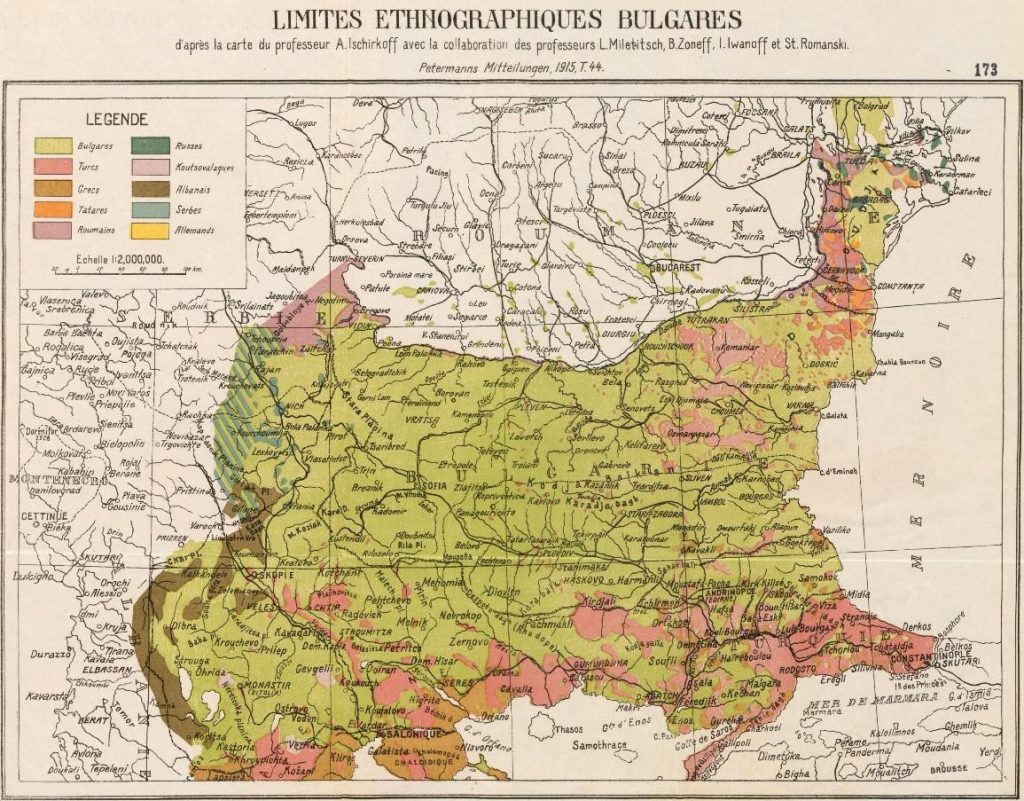

Despite strong support from the Americans, Bulgaria had to accept defeat in every territorial question. Macedonia, ruled by the Ottomans until their expulsion in 1912, and mostly divided between Greece and Serbia after Bulgaria’s defeat in 1913, was not discussed at all, despite its large Bulgarian majority; the ethnographical map submitted by the delegation in 1919 depicted almost every part of Macedonia as Bulgarian (see below, in green). On this western side of the country, only the Serbian demand for parts of Bulgaria – slivers of land that would make Serbia (Yugoslavia) less vulnerable to another Bulgarian attack – was considered. As both Bulgarians and Americans contended, the population involved was almost wholly Bulgarian. At Tsaribrod, for example, there were nearly 42,000 Bulgarians and only 93 Serbs. The salient at Strumitza was also Bulgarian; when Foreign Secretary Balfour asked an aide, Harold Temperley, “Who are the inhabitants?” his answer was, “Undoubted Bulgars.”[8] Nevertheless, the strategic argument prevailed and Tsaribrod, Strumitza and Bosilegrade were all given to Serbia.

Southern Dobrudja, a rich area in north-eastern Bulgaria that the Romanians had seized from Bulgaria in 1913 (but lost in 1916), contained an estimated 122,000 Turks, 112,000 Bulgarians, 10,000 Tartars and 7,000 Romanians. Romania “lacked even a passing ethnical claim to the area”.[9] Even the Romanophile French geographer, Emmanuel de Martonne, did not indicate that the area was Romanian (red). No-one in Paris contemplated returning a part of Europe to the Turks, so the Americans urged that, according to the nationality principle, Southern Dobrudja should be returned to Bulgaria. The British and French insisted, however, that, “Romanians should not be left with the feeling that they have been “robbed” by their Allies to placate their enemies.”[11] Neuilly confirmed Romania, the wartime ally of the Western Powers, in possession.

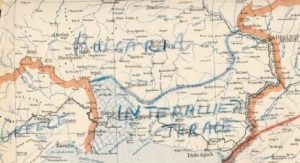

The population of Western Thrace, in the south, was much more mixed, most assessments giving the Turks the largest number, followed by Bulgarians, and then Greeks. Neuilly awarded Western Thrace to the Allies collectively, and it was run for six months by an Inter-Allied Administration, but it was transferred to Greece at the San Remo  conference of April 1920.[12] The Bulgarian argument (backed by the Americans in 1919) that this denied them access to the Aegean Sea – “Bulgaria cut off from the Aegean will be breathing with one lung”[13] – was met with Greek assurances that the Bulgarians could use their ports: “If Bulgaria is given guaranteed outlets at Kavalla and Dedeagatch she cannot complain that ais being strangled.”[14] Above all, Bulgaria “was the enemy of France, Great Britain and Greece and it would be absolutely unjust to confer these advantages on their former enemy…”[15]

conference of April 1920.[12] The Bulgarian argument (backed by the Americans in 1919) that this denied them access to the Aegean Sea – “Bulgaria cut off from the Aegean will be breathing with one lung”[13] – was met with Greek assurances that the Bulgarians could use their ports: “If Bulgaria is given guaranteed outlets at Kavalla and Dedeagatch she cannot complain that ais being strangled.”[14] Above all, Bulgaria “was the enemy of France, Great Britain and Greece and it would be absolutely unjust to confer these advantages on their former enemy…”[15]

As well as finding against Bulgaria in the territorial settlement, the treaty required the country to disarm. The draft treaty in September 1919 limited Bulgaria’s army to 20,000 men, but this was amended to allow a frontier guard (of up to 3,000 men) and the retention of a small number of lightly-armed boats for police and fishery duties on the Danube and the Black Sea coast. The army was to be held at 20,000, but the maximum total strength of the armed forces, including 10,000 gendarmes and the 3,000 frontier guards, was set at 33,000. However, Bulgaria’s principal complaint – that she required some element of compulsory service, on the grounds that the country’s mostly peasant population would never yield an adequate number of volunteers – was overruled. The original reparations bill of 2 milliard 250 million gold francs (£90 million), tens of thousands of farm animals and 250,000 tons of coal was unaltered, despite Bulgarian objections that it was beyond the country’s capacity to pay, but the annual payment was reduced. “Proportionate to its size and GDP, Bulgaria faced the highest reparations bill of all the Central Powers.”[17]

The British and French rewarded their Romanian, Serbian and Greek allies at the expense of defeated Bulgaria. It was in the spring months of 1919 that the Americans allowed Britain and France to seize the initiative and make provisional decisions that Frank Polk, head of delegation from late July, struggled in vain to undo. Irrespective of their ideas on individual issues, however, even the Americans felt no sense of commitment to Bulgaria’s cause. Woodrow Wilson’s August 1919 view that Bulgaria “deserves no consideration whatever at our hands” and Polk’s acceptance of the contrast between Bulgaria’s “unjust war” and the just war fought by Greece reveal the underlying lack of sympathy.[18] When most of the European countries resumed diplomatic relations with Bulgaria in 1920, Wilson’s opinion, setting aside the breezy flippancy, was nakedly hostile:

Personally, I feel disinclined to appoint a Minister to Bulgaria. I have found the Bulgarians the most avaricious and brutal of the smaller nations that had to be dealt with in the war and in the settlement of the terms of peace, though for a time my vote was for Roumania in those respects. Being no longer committed to Roumania, I can perhaps transfer my suffrages to Bulgaria.[19]

There was an absence of the moral fervour that inspired Wilson’s policy elsewhere, permitting acquiescence in a Bulgarian treaty in which no American had any confidence.

Bulgarian fury

With Bulgaria reduced and her rivals vastly expanded, the balance of power was transformed. Their enemies had long spoken of Bulgaria as “the Prussia of the Balkans” – but if the Balkans had a Prussia now, it was not Bulgaria. Bulgarians bewailed the Second National Catastrophe (the first being their defeat in the Second Balkan War in 1913). The first manifestation of the popular reaction was seen on 30 September 1919, in response to the draft treaty, when thousands marched through Sofia, many dressed in black to mark the “day of national mourning”. They wielded placards which asked, “Where are Justice and the Protection of small nations?” and demanded “a Plebiscite in Thrace, Macedonia and Dobrudja. This unjust and destructive peace will cause a great precipice between us and our neighbours and render a lasting peace in the Balkans impossible.”[20] Colonel Sir Harry Lamb, one of Britain’s representatives in Sofia, reported that the peace terms were greeted with “stupefaction”, “incredulity” and “an overwhelming sense of suffocation”.

As one Bulgarian put it to me, “The Powers claim to have settled one Alsace-Lorraine question in Western Europe, but they have replaced it by a new one which they have created in the Near East. Tzaribrod will be the Strasbourg of Bulgaria and our children will be taught to dream of its reconquest.”

… The bitterest vituperation is reserved for President Wilson… “We were told,” said another Bulgarian, “to expect a peace based on Justice and you have given us a peace of revenge…”[21]

Lamb was sure that a great error had been made by imposing a peace which would leave the Bulgarians infuriated and determined to fight another war at the first opportunity.[22] Nadejda Stanciov wrote privately of the anguish of the delegates, but her words give succinct expression to the general Bulgarian sentiment: “We are staggered, petrified, crushed… [There is] “no justice or equity for the defeated”.[23]

Aftermath

Southern Dobrudja

The peace settlement left thousands of Bulgarians under foreign rule and gave rise to huge demographic change as people flocked into Bulgaria as refugees. In fact, the population movement began a year before Neuilly, at the end of the war. In April 1919, Harry Lamb estimated that Bulgaria had “from 2 to 300,000 refugees from Macedonia and probably over 100,000 from Thrace and perhaps 20,000 from the Dobrudja, awaiting a decision of the Peace Conference that will permit of their returning home”.[24] According to the Bulgarian delegation in September 1919, after the Romanian army entered Southern Dobrudja in August, “the Bulgarian schools are closed, Bulgarian priests and teachers have been driven away and replaced by Roumanians. Hundreds and hundreds of native Bulgarians have been prosecuted, imprisoned and deported by the Roumanian authorities and thousands of others – their number at the moment exceeds 15,000 souls – have been forced to emigrate [from the Dobrudja] to Bulgaria.” Teodor Teodorov, the outgoing Prime Minister, accused the French of “facilitating the expulsion en masse of the Bulgarians”. He denied Romanian claims that Bulgarian irregulars (“comitadjis”) were raiding across the Bulgarian border, but the British Military Representative in Sofia later reported that the “Dobrudja Society” had armed hundreds of refugees “to carry out occasional rushes on the frontier” and quoted one refugee, presumably untypical, who said that, “No Dobrudjan ought to die before he has butchered two Roumanians.”[25]

Romania (like six other new or expanded states) signed a Minorities Treaty in Paris in which the rights of national minorities were guaranteed. However, the Romanians resented a measure that, they argued, infringed their sovereignty and they signed only on the insistence of the Council. In the 1920s, citing irredentism and incursions by “comitadjis”, they treated the Dobrudjan Bulgarians like a conquered enemy. Bulgarian cultural institutions, churches and schools were closed down, forcing the Romanian language on worshippers and students and establishing Romanian schools that were bereft of Romanian children. Petitioners in favour of Bulgarian schools were “arrested, mishandled, and forced to declare that they were content with Roumanian schools”.[26] An agrarian law to redistribute land was used to expropriate Bulgarians’ property for the benefit of incoming Romanians, establishing, in the words of one Bulgarian account, “un système de spoliation des immeubles, dans le but bien défini de priver les Bulgares de tous leurs biens, de les ravaler au rang de serfs.” Between one-third and a half of Bulgarian (and Turkish) land was confiscated and “distributed to Rumanian immigrants”. The state’s policy, Georgi Genov alleged, was designed either to effect “the Rumanization of the Bulgarian minority” or “to expel them beyond the frontier”.[27] According to a modern estimate, 36,000 emigrated from Southern Dobrudja to Bulgaria in the inter-war years.[28] Genov was a partisan Bulgarian, but the League’s Pablo de Azcárate, a Romanophile, wrote in very similar terms of the Romanian government’s “unfortunate attempt to “denationalize” the Bulgarian peasants … by means of a kind of forced colonization of Rumanian peasants in the territory”. Bulgaria made formal complaints to the League of Nations and non-government institutions in Southern Dobrudja presented petitions against Romanian oppression.[29]

Notwithstanding this, however, the intense conflict of the early days probably eased with the passage of time. Prime Minister Stamboliĭski’s visits to Romania in the early 1920s may have brought “a certain amelioration” of the problem.[30] François Bocholier has described a state of tension that fell some way short of outright persecution: “Il n’y a pas de massacres ou de terreur roumaine… mais plutôt de continuelles pressions et tracasseries [pressure and harassment] sur les populations locales, qui répondent par la contrebande et la désobéissance civile.”[31] After the death of Romania’s Ionel Brătianu in 1927, there was an attempt to appease the Bulgarian community: “Nous avons des déclarations officielles … qui détournent le visage de honte, et réclament un regime d’apaisement et de justice dans cette malheureuse province.”[32] A number of Bulgarian cultural institutions and private schools, some of them subsidised by Sofia, were permitted and in 1932 the teaching of Bulgarian was permitted again in state schools. Most Bulgarians did not emigrate: the influx of Romanians – almost 70,000 were moved into the area in ten years – meant that the Bulgarians declined as a share of the population (to 38%), but the 1930 census showed that the absolute number of Bulgarians in Southern Dobrudja went up in the 1920s, to just over 140,000 persons, still outnumbering the Romanians.[33] This helped to make the subsequent reversion to Bulgaria feasible.

Western Thrace

The outcome was very different in Western Thrace. The Bulgarians clearly feared atrocities at the hands of the Greeks and in July 1919, in anticipation of a Greek takeover, the “prudent” were “already sending their wives, families and valuables into Bulgaria”. After the Greek army arrived in October, Harry Lamb reported a “sudden inrush of refugees” into Bulgaria. “Upwards of 10,000 Bulgars are reported to have left Xanthi and several thousands more have fled from Gumuldjina [Komotini] and Dede-Aghatch. Many of these people, of course, were not natives of these places, but were already refugees from Macedonia who are now moving one stage further from their original homes. A good many Turks have also quitted the evacuated district and moved further north into the hills…”[34] Lamb went on to give an insight into the plight of the refugees:

The evacuation of Xanthi appears to have been effected without disorder. The time allowed was so short that there was necessarily considerable congestion and consequent suffering (people camping round the railway station for days, awaiting their chance of a passage) and loss (people selling their furniture and other property, which they were unable to remove, at nominal prices) but no disturbances have been reported, nor did I anticipate that there would be, so long as Allied troops are on the scene. The trouble will only begin later, when these are withdrawn and the Greek authorities are left face to face with the population. Our Officer down there estimates the number of refugees who have fled from Xanthi and its immediate neighbourhood at 25,000, of whom 18,000 may have been Bulgars and the remainder Turks, Jews and a few non-descripts. About 4,000 Bulgars, according to his calculation, still remain to face the Greeks.[35]

At the end of January 1920, there were “very few Bulgarians left” at Xanthi, the part occupied by Greek troops, and the Greeks were held to be “very obviously making an attempt to colonise not only the Xanthi district but also the whole of Inter-Allied Thrace, chiefly at the expense of the Bulgarians. All along the line between Souflou and Xanthi one finds railway waggons full of these Greeks, and some of them do not know where they are going to or who sent them… Up to date about 5,000 Greeks have been imported into [the] Xanthi area alone, and colonisation of the whole of Inter-Allied Thrace is also steadily going on in this way.”[36] Many of these incomers, numbering as many as 51,000 in one account, were returning Greeks who had fled from the Bulgarian takeover in 1912-13.[37] The Inter-Allied Administration (until the handover to Greece) established arbitration commissions, but even an admirer of their efforts conceded that they restored returning Greeks to their property at the expense of Bulgarians: “Most of their decisions were of necessity given against Bulgarian nationals.”[38]

Full Greek control of Western Thrace from May 1920 worsened the position of the Bulgarians. Prime Minister Venizelos had signed the Minorities Treaty for Greece in September 1919 but, echoing Brătianu, he denounced it as “derogatory to the sovereignty of Greece”. The attribution of rights, he said, would “imperil the loyalty” of minorities and he was particularly critical of the requirement that Bulgarian children in Greece should receive instruction in their own tongue.[39] High-minded ideas of protection of minorities perished in the heat of nationalist egos and ethnic tensions. Ellen Garrett described systematic persecution of Bulgarians in the 1920s, involving closure of their schools and churches, proscription of the Bulgarian language, forced billeting of sometimes brutal soldiers, direct expulsions across the frontier, and (for a short time) the conscription of young men to fight the Turks in Asia Minor.[40] The most serious incident was the “Tarlis Massacre” of July 1924. Tarlis was a Bulgarian village on the Greek side of the border. Greek militiamen were fired upon there on 27 July and, in response, between 60 and 70 Bulgarian males were arrested, 27 were bound and marched into the hills and 17 of these were shot while trying, it was claimed, to escape.[41] An international outcry caused the Bulgarians and Greeks to sign the Politis-Kalfov Protocol by which neutral agents would be on the ground to monitor the treatment of minorities, but this protocol, which might have made the Minorities Treaty effective, was unanimously rejected by the Greek Parliament in February 1925 as “interference in the internal affairs of the State”.[42] Venizelos’s defence of this decision was described by a British Quaker as “a speech whose cynical levity and insolence can rarely have been exceeded in the history of the League”.[43]

Neuilly had provided for the “reciprocal and voluntary emigration of persons belonging to racial minorities” in Greece and Bulgaria and, accordingly, a convention was concluded between the two countries for an exchange of populations. However, Bulgarians fled without recourse to the formal procedures, driven out “sous la menace de la mort… cela s’appelle, par euphémisme, ‘l’émigration voluntaire’.”[44] It “was made sufficiently plain to the Bulgarian that the Greek intruder was master there, and nothing was left to him but to go” – so that southern Bulgaria was filled with “a ragged and destitute host”.[45] After the fall of Smyrna in September 1922, the Greeks fled from Asia Minor and Eastern Thrace and many were brought to Greek Macedonia and Western Thrace and “the settled “minorities” [there] felt increasingly forced to depart”.[46] At Lausanne in January 1923, the compulsory exchange of Orthodox and Muslim populations was agreed between Greece and Turkey. The exclusion of Western Thrace Muslims from this agreement probably increased pressure on the Bulgarian minority, for it was not the region’s Muslims who had to make way for incoming Greeks.[47] Almost 12,000 Bulgarians left Greece in 1923 and the figure rose to 27,577 in 1924 and 21,123 in 1925.[48]

The fate of Bulgaria’s Greeks was, in the end, not dissimilar. Most of them were initially hesitant to leave Bulgaria, despite the closure of Greek schools and the way in which Stamboliĭski’s land reforms dispossessed many Greeks. Then, however, Greek policy in Western Thrace (after Smyrna and Lausanne) led to “reciprocal repressive measures” against Greeks in Bulgaria (“retaliation for the expulsion of Bulgarians from Western Thrace”). These measures often involved Greeks being forced to vacate their homes to make way for incoming Bulgarians. Many of the latter, destitute and aggrieved, became lawless brigands and were responsible for violence and threats against Greeks. This prompted a wave of Greek emigration in 1924-25, the number of Greeks in Bulgaria falling from 46,759 in 1920 to 12,782 in 1926 and only 9,601 in 1934.[49] Facing mistreatment on both sides of the border, Greeks and Bulgarians fled to the safety of their national states. As Dragostinova observed, the Convention for Voluntary and Reciprocal Emigration of Minorities “proved to be more reciprocal than voluntary”.[50] In the 1928 census, the Bulgarian population of Western Thrace was only 1,059 and in 1951 it was eight. This partly reflected the practice of counting all Orthodox Christians as Greeks, and there were Bulgarians who had learnt the wisdom of keeping quiet about their identity.[51] But Macartney accepted the figures at face value: Western Thrace “was ultimately cleared completely of its Bulgarian population – a fact which Greece, at any rate, will count as a gain”.[52]

The Western Outlands

In the lands lost to Serbia, which Bulgarians began to call the Western Outlying Parts (or Western Outlands), there were Serb accusations in 1919 that the Bulgarian authorities in some places armed civilians and encouraged them to resist the transfer.[53] Soon, however, the Bulgarians were accusing the Serbs of installing a reign of terror (“une orgie de sang”) in which people were murdered, teachers and priests were arrested, and scores of schools and churches were closed or simply Serbianised in terms of personnel and language.[54] By the “severe Serbification policy” imposed by Belgrade, “Petrovs and Popovs were required to become Petroviches and Popoviches”.[55] There was an exodus of Bulgarians, encouraged by Serbia: “ils ne souffrent pas de Bulgares dans leur royaume.”[56] Reliable statistics are not available, but the number reached well into the thousands; Strumitza already held 8-10,000 refugees from Macedonia and in October 1919 Teodorov expected all of them to move on again, into Bulgaria.[57] Most settled in south-western Bulgaria where, in 1934, Patrick Leigh Fermor found that “prominent on many walls were maps illustrating the terra irredenta that Bulgaria claimed from her neighbours: lumps of Yugoslavia, the Dobrudja in Rumania and, preposterously, Greek Macedonia including Salonika.”[58]

The total number of refugees who entered Bulgaria after the war is not known with any certainty. A contemporary map now on display in the National History Museum in Sofia claimed that 650,000 Bulgarians left Macedonia (including the newly transferred western lands), 400,000 arrived from Western Thrace and 50,000 left Dobrudja. Other, more circumspect estimates put the total number at nearly half a million, about ten per cent of Bulgaria’s population.[59] The influx created the so-called “demographic crisis” of the postwar years, with concentrations of destitute people in border areas and major cities (“une veritable invasion … une avalanche de milliers d’hommes, d’enfants, de femmes” who suffered “les privations, l’épidémie et la famine”).[60] Many spent years living in squalid conditions in refugee camps. Stamboliĭski’s radical government (1919-23) forced urban property owners to accept tenants, including refugees, at controlled rents, municipalities gave refugees plots to build houses, and the land reform benefited 28,500 refugees.[61] But Bulgaria lacked the financial means to cope with the problem and Lady Muir estimated at the end of 1926 that “there remain some 150,000 to be installed who are now living in great misery and on the verge of starvation”. Their “wretched plight” was ameliorated when the League of Nations raised an international loan in 1926 which was used to fund the resettlement of refugees; this allowed the reduction of the refugee population in Pirin by one-third.[62] In due course, the refugees were dispersed throughout the country, and today it is still possible to see street and district names (Prilep, Ohrid, Tsaribrod, Dobrudja and so on) that recall people’s origins.[63]

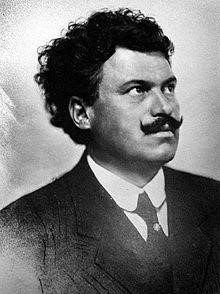

The revisionists

Prime Minister Stamboliĭski (right) believed that Neuilly would “not be destroyed by the sword” but by “an indignant world conscience”.[64] Anticipating by some years the “fulfilment” policy of Stresemann’s Germany, he tried to improve relations with Bulgaria’s neighbours and the Western Powers – an effort which included a 100-day European tour towards the end of 1920 – and led his country into the League of Nations in December 1920, the first defeated state to be admitted.[65]

Bulgaria began to pay reparations or, when she was unable (1920, 1922), arranged a moratorium. He negotiated a reduction of the burden in 1923; in a foretaste of the famous Young Plan for Germany, the total amount was cut and payment was phased over 60 years to 1983. The bill was reduced again in 1929, a little-known part of the Young Plan, before payments were suspended under the Hoover Moratorium of 1931 and never resumed; Bulgaria’s reparations bill was finally cancelled in 1936.[66]

Other aspects of Stamboliĭski’s policy were more controversial. The refugee communities were outraged that he appeared too accepting of the territorial losses of 1919. These communities became the breeding ground of terrorism: the Macedonians formed the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organisation (IMRO), reviving an organisation that had begun in 1893 as an enemy of Ottoman rule. The Internal Western Outland Revolutionary Organisation (a subsidiary) operated in Tsaribrod and Bosilegrad, their Thracian equivalents established the Internal Thracian Revolutionary Organisation (ITRO), and the Dobrudjans formed the Internal Dobrudjan Revolutionary Organisation (IDRO). The IMRO committed hundreds of political murders in the inter-war years, launching cross-border raids from their main base at Petrich (in Pirin, south-western Bulgaria, where the Yugoslav, Greek and Bulgarian frontiers met) to attack targets, notably the railway line to Belgrade, bridges, barracks and state officials, in both Yugoslavia and Greece.[67] Although ethnically Bulgarian, for most the goal was an autonomous Macedonia rather than union with Bulgaria. The ITRO was in open rebellion against the Greeks during the years (1922-24) of greatest pressure on the Bulgarians of Western Thrace, and the IDRO conducted a less violent campaign against the Romanian authorities in Southern Dobrudja.

IMRO violence was extended to opponents within Bulgaria and they murdered the Minister of War in 1921 after he tried to purge the army and frontier police of IMRO members. On 23 March 1923, Bulgaria and Yugoslavia signed the Treaty of Niş, by which Bulgaria accepted its territorial losses to Yugoslavia and the two countries agreed to cooperate in suppressing the IMRO. In April, all terrorist organisations in Bulgaria, including the IMRO, were declared illegal. However, a right-wing coup overthrew the Prime Minister in June 1923 and the IMRO then captured, tortured and murdered him: Stamboliĭski’s ears were sliced off, his hand, the one that had signed the Treaty of Niş, was cut off, and his head was sent to Sofia in a biscuits tin.[68] Richard Crampton has written of the “terrible price” that had to be paid for this coup: “The Macedonians were to have another eleven years in which to threaten, to kill and to blacken Bulgaria’s name…”[69] IMRO activity on the Greek border caused one of the tests faced by the young League of Nations: the Greek army crossed the frontier to confront the terrorists in 1925 and it was resisted by the IMRO and their allies in the local Petrich militia, until the League intervened to order the Greeks to withdraw. The resultant Commission of Inquiry attributed the affair to the presence of refugees who were “looking forward either to returning to their own homes or avenging themselves on those who had driven them out, or both… The [Greek] inhabitants of the settlements near the frontier lived in constant dread of reprisals.”[70]

The subsequent dispersal of the refugees may have eased tensions on the borders, but IMRO terrorist violence continued in the succeeding years and there were murderous feuds within the organisation. It came to the world’s attention with the assassination of King Alexander I of Yugoslavia in Marseilles in 1934 – he was shot by IMRO activist and notorious killer Vlado Chernozemski – carried out in collaboration with the Croatian Ustaše. Patrick Leigh Fermor was in Tŭrnovo in northern Bulgaria to witness the celebrations – “laughing and stamping, hugging and kissing… “They’ve killed the Serbian King! Today in France! And it was a Bulgar that did him in!”” – prompted by this news.[71] However, the IMRO was riven with division, and its Petrich regime was run by gangsters who trafficked opium and extorted money from the inhabitants. Most Bulgarians were relieved when, also in 1934, their own army assailed the Petrich stronghold and the organisation was driven underground, never to recover its former strength.

Neuilly undone

Despite pressure from terrorists and the refugee communities, all of the interwar governments of Bulgaria pursued a policy of peaceful revisionism. In 1937, Yugoslavia agreed a Treaty of Eternal Friendship with Bulgaria and in 1938 Bulgaria and her neighbours signed the Salonica Agreement, annulling the military restrictions of Neuilly. By this stage, the principal question facing the smaller European countries was the nature of their relationship with Nazi Germany. The mid to late 1930s saw Bulgaria’s growing (and beneficial) economic dependence on Germany. Hitler, seeking an alliance with Bulgaria, compelled the Romanians to return almost all of Southern Dobrudja to Bulgaria in the Treaty of Craiova of September 1940. The treaty provided for a compulsory exchange of populations: by December, all of the area’s Romanians had moved to Romania, and the 60,000 Bulgarians in Northern Dobrudja were despatched to Bulgaria.[72] In March 1941, under overwhelming pressure from the Germans, Bulgaria became a member of the Axis.[73] After King Boris met Hitler in Vienna on 19 April, the Bulgarians followed the Germans into Yugoslavia and Greece, occupying Macedonia and Western Thrace, prompting popular “jubilation at the sudden achievement of complete national union”.[74] The Bulgarians encountered a mixed reception in Macedonia: they were welcomed by some – “One people, one Tsar, one kingdom” was the Hitler-inspired message on a banner raised in Skopje – but they soon found that many of the younger generation resented Bulgarian domination.[75] Western Thrace witnessed savage repression designed to encourage the Greeks to emigrate and clear the way for Bulgarians; there was armed resistance from the Greeks, which caused “unusual atrocities” by the Bulgarian army.[76]

Although the Bulgarians refused to join the attack on Russia, and never actually fought against the Western Allies, Bulgaria was invaded and conquered by the Red Army in September 1944 and forced to withdraw immediately from Macedonia and Western Thrace. Under a Communist-dominated government, the Bulgarians went on to play a significant military role against the Germans in Yugoslavia and Hungary. Bulgaria was permitted to retain Southern Dobrudja when the Paris Peace Treaties of 1947 reaffirmed the border of 1940. The Romanians (or at least their leaders) had been much more enthusiastic allies of Nazi Germany than Boris and the Bulgarians – “Romania gave greater military support to Germany against the Soviet Union than did any other Axis ally”[77] – so the position was very different from that of 1919, and, in addition, the population transfers had created a demographic fait accompli.[78] Bulgaria emerged from World War II as the only Axis country that gained territory. No longer pariah (Bulgaria’s sins were relatively minor, set against the horrors of the Second World War), no longer Prussia, Bulgaria and her people finally received a more just settlement than that of 1919. But they got Stalin as well. Patrick Leigh Fermor, contemplating Bulgaria’s modern history, was less than sympathetic:

Bulgarians have a perverse genius for fighting on the wrong side. If they had been guided more by their hearts and less by their political heads, which usually seem to have lacked principle and astuteness in equal degrees, their history might have been a happier one.[79]

Bulgarians did adhere to a principle, that of a united nation-state, but it was pursued through aggressive and destructive war. Between them, principled war and an unprincipled peace determined Bulgaria’s unhappy fate. The 20th century was a disaster from which today’s Bulgaria is just beginning to recover.

[1] For two scathing assessments of the wartime role of Bulgaria, see Harold Nicolson, Peacemaking 1919 (London, 1933), 334-35 (“perfidy”) and Notes of Meetings of the Heads of Delegations of the Five Great Powers, National Archives, CAB 29/70, 124, 31 July 1919, Balfour (“cynical” and “disastrous”).

[2] Lord Vansittart, The Mist Procession: The Autobiography of Lord Vansittart (London, 1958), 229.

[3] G.P. Genov, Bulgaria and the Treaty of Neuilly (Sofia, 1935), 25, 48-9. Mari A. Firkatian, Diplomats and Dreamers: The Stancioff Family in Bulgarian History (Lanham, 2008), 191-94 (“lions” – Nadejda Stanciov).

[4] Heads of Delegations, CAB 29/74, 265, Reply of the Allied and Associated Powers to the Observations of the Bulgarian Delegation on the Conditions of Peace, 1 November 1919.

[5] Heads of Delegations, CAB 29/74, 254-6, 258, 267, 1 November 1919. H.W.V. Temperley, ed., A History of the Peace Conference of Paris (London, 1921), IV, 415.

[6] Papers of Allen Leeper (LEEP), 1/2, 96, Leeper’s Diary, 27 November 1919.

[7] Isaiah Bowman in E.M. House and C. Seymour, eds., What Really Happened at Paris: The Story of the Peace Conference, 1918-1919 by American Delegates (London, 1921), 163-64. The photograph appeared in L’Illustration, 6 December 1919.

[8] T. G. Otte, ed., An Historian in Peace and War: The Diaries of Harold Temperley (Farnham and Burlington, 2014), 418-19, 16 May 1919.

[9] Michael L. Dockrill and J. Douglass Goold, Peace without Promise: Britain and the Peace Conferences, 1919-23 (London, 1981), 97. Leeper concurred in an estimate which had 105,000 Turks, 135,000 Bulgarians and 6,000 Romanians. Foreign Office Papers, FO 608/34, 228, note by Leeper, 25 January 1919.

[10] Repartition des Nationalités dans les pays ou dominant les Roumains, par, FO 371/3566, 562.

[11] FO 608/34, 230, note by Leeper, [6] February 1919; FO 608/48, 383, note by Leeper, 25 January 1919.

[12] The map is an improvised view of Inter-Allied (Western) Thrace. FO 371/3574, 484, note by Howard Smith, 19 January 1920.

[13] FO 608/31, 322, Minute by Heard, 15 March 1919.

[14] FO 608/37, 41, Greek Claims at the Peace Conference, 28 January 1919 (Crowe and Nicolson). See also FO 608/31, 254, Leeper’s annotation (6 May) on Heard to Leeper, 6 April 1919.

[15] FO 608/55, 25, Nicolson to Crowe, 11 July 1919.

[16] Limites Ethnographiques Bulgares, 1915, FO 371/3573, 173.

[17] Robert Gerwarth, The Vanquished: Why the First World War Failed to End, 1917-1943 (London, 2016), 209. Neuilly was the only treaty in which the amount of reparations was specified.

[18] Arthur S. Link, ed., The Papers of Woodrow Wilson (Princeton, 1989), Volume 62, 141, Wilson to Lansing, 4 August 1919; ibid., 328, Polk to Lansing, 16 August 1919;

[19] Ibid., Volume 66, 367, Wilson to Colby, 15 November 1920.

[20] FO 608/32, 191, Report of the British Military Representative at Sofia, 14 October 1919.

[21] Ibid., 239, Lamb to Curzon, 27 September 1919.

[22] America’s Isaiah Bowman also warned that the treaty “guaranteed a future war”. Arthur Walworth, Wilson and his Peacemakers: American Diplomacy at the Paris Peace Conference, 1919 (New York and London, 1986), 467, citing Day Papers, Bowman to Day, 4 November 1919.

[23] Firkatian, Diplomats and Dreamers, 201, journal entry for 3 November 1919.

[24] FO 608/32, 371, Lamb to Oliphant, 19 April 1919. Most of the Macedonian refugees had arrived in 1913.

[25] FO 608/32, 155, Teodorov to Clemenceau, 6 September 1919; ibid., 191, Report of the British Military Representative at Sofia, 14 October 1919 (Baird).

[26] C. A. Macartney, National States and National Minorities (Oxford, 1934), 418.

[27] Les droits des minorités bulgares et la Societé des Nations, par un minoritaire bulgare (Lausanne, 1929), 33, 58-9. Genov, Bulgaria and the Treaty of Neuilly, 165-67, 179-80.

[28] Blagovest A. Njagulov, ‘La Protection Internationale des Minorités au XXeme Siècle: Le Cas Bulgaro-Roumain’, New Europe College Yearbook (2002), Issue 10, 71, 81.

[29] P. de Azcárate, League of Nations and National Minorities (Washington, 1945), 48.

[30] Stanka Georgieva review of Stefan Ancev, Le problème de Dobrudza dans la vie de la Bulgarie durant la période 1918-1923, in Bulgarian Historical Review (1996), Issue 1, 144.

[31] François Bocholier, ‘La Dobrudja entre Bulgarie et Roumanie (1913-1919): regards Français’, Études balkanique (2001), Issue 2-3, 76.

[32] Les droits des minorités bulgares, 60-1.

[33] Sabin Manuila, La Population de la Dobroudja, in Académie Roumaine, Connaissance de la Terre et de la Pensée Roumaine, IV, La Dobroudja (Bucharest, 1938), 460-2.

[34] FO 371/3573, 185, Lamb to Oliphant, 21 July 1919. FO 608/55, 254, Lamb to Curzon, 17 October 1919.

[35] FO 608/33, 76, Lamb to Oliphant, 21 October 1919. “The state in which these unfortunates are is indescribable…” Heads of Delegations, CAB 29/74, 54-5, Teodorov to Clemenceau, 21 October 1919 (also in FO 608/32, 273).

[36] FO 371/3574, 600, Neate to the Director of Military Intelligence, War Office, 31 January 1920. See also ibid., 609, Dering to Curzon, 6 February 1920, enclosing Captain F.P. Baker’s intelligence report of 2 February 1920.

[37] Stephen P. Ladas, The Exchange of Minorities: Bulgaria, Greece and Turkey (New York, 1932), 16.

[38] David Mitrany, The Effect of the War on Southeastern Europe (New Haven, 1936), 256-7, 260-61.

[39] FO 608/150, 234, Venizelos to Berthelot, 31 July 1919; ibid., 254, Draft Report to the Supreme Council on the Greek Treaty. Heads of Delegations, CAB 29/74, 330-31, 3 November 1919.

[40] Ellen Garrett, ‘The Recent History of West Thrace’, The Contemporary Review (1 January 1923), Vol. 123, 62-63.

[41] L.P. Mair, The Protection of Minorities: The Working and Scope of the Minorities Treaties under the League of Nations (London, 1928), 177-79. Les droits des minorités bulgares, 57, “le but de terrifier les bulgares et de les forcer à émigrer.”

[42] Theodora Dragostinova, Between Two Motherlands: Nationality and Emigration among the Greeks of Bulgaria, 1900-1949 (Cornell, 2011), 144-47.

[43] Horace G. Alexander, The League of Nations and the Operation of the Minority Treaties (London, 1926), 9.

[44] Les droits des minorités bulgares, 33, 55-56. See also Macartney, National States and National Minorities, 440-41. Charles B. Eddy, Greece and the Greek Refugees (London 1931), 250-51. By June 1923, only 197 Greek and 166 Bulgarian families had applied to emigrate under the convention. Dimitrije Djordjević, Migrations during the 1912-1913 Balkan Wars and World War One’, in Migrations in Balkan History (Belgrade, 1989), 120.

[45] Garrett, ‘The Recent History of West Thrace’, The Contemporary Review (1 January 1923), Vol. 123, 63.

[46] Jane K. Cowan, ‘Fixing National Subjects in the 1920s Southern Balkans’, American Ethnologist (May 2008), Vol. 35, No. 2, 345-46.

[47] Bruce Clark, Twice a Stranger: How Mass Expulsion Forged Modern Greece and Turkey (London, 2006), 148-49, 162-63.

[48] Dragostinova, Between Two Motherlands, 142, 144, 147.

[49] Joseph Rothschild, East Central Europe between the Two World Wars (Seattle and London, 1974), 328. Mair, The Protection of Minorities, 176-77. Theodora Dragostinova, ‘Speaking National: Nationalizing the Greeks of Bulgaria, 1900-1939’, Slavic Review (Spring 2008), Vol. 67, No. 1, 165-6. Dragostinova, Between Two Motherlands, 117-18, 131-32, 137 et passim. The “retaliation” line came from a Bulgarian official in September 1923. Ibid., 143.

[50] Ibid., 154.

[51] The Greeks take a more positive view: “The slavophones that remained in Greece declared Greek ethnicity… [and] considered themselves nothing else but Greeks.” George C. Papavizas, Claiming Macedonia: The Struggle for the Heritage, Territory and Name of the Historic Hellenic Land, 1862-2004 (Jefferson, North Carolina and London, 2006), 85.

[52] Macartney, National States and National Minorities, 441. “There are no Bulgarians left in Western Thrace.” Ladas, The Exchange of Minorities (1932), 123.

[53] FO 608/32, 235, 307, Athelstan-Jones to Curzon, 1, 2 October 1919.

[54] Les droits des minorités bulgares, 54-5. Genov, Bulgaria and the Treaty of Neuilly, 156-7. Alexander, The League of Nations and the Operation of the Minority Treaties, 7.

[55] L. S. Stavrianos, The Balkans since 1453 (New York, 1965), 649.

[56] Les droits des minorités bulgares, 55.

[57] FO 608/32, 279, Teodorov to Clemenceau, 23 October 1919.

[58] Patrick Leigh Fermor, The Broken Road: From the Iron Gates to Mount Athos (London, 2013), 18.

[59] Djordjević had only 251,309 refugees in Bulgaria in the 1920s, “of whom 121,677 came from Greece, 31,427 from Yugoslavia, 70,294 from Turkey and 29,711 from Rumania.” Djordjević, ‘Migrations during the 1912-1913 Balkan Wars and World War One’, in Migrations in Balkan History, 121.

[60] Les droits des minorités bulgares, 34, 64.

[61] Ivan Ilchev, The Rose of the Balkans: A Short History of Bulgaria (Colibri, 2005), 321. Stevan K. Pavlowitch, A History of the Balkans, 1804-1945 (London and New York, 1999), 243.

[62] John R. Lampe, Balkans into Southeastern Europe, 1914-2014: A Century of War and Transition (Basingstoke, 2014), 86. Nadejda (Lady) Muir, ‘The Present Position of Bulgaria’, Journal of the Royal Institute of International Affairs, Vol. 6, No. 2 (March 1927), 94-97.

[63] Sofia grew from 95,000 before the war to 200,000 by 1929 and “30,000 of that increase came from the refugees driven in from Vardar and Aegean Macedonia by the peace settlement. Their cramped and ramshackle quarters on the city’s western edge were the scene for factional violence throughout the decade…” Lampe, Balkans into Southeastern Europe, 101.

[64] R. J. Crampton, Aleksandŭr Stamboliĭski: Bulgaria (London, 2009), 85, quoting Stamboliĭski.

[65] Sir Maurice Hankey thought Stamboliiski “a cutthroat looking brigand” when the Bulgarians visited London in October 1920. Hankey Papers, 1/5, Diary, 30 October 1920.

[66] Crampton, Aleksandŭr Stamboliĭski, 98-101, with 1921 and 1923 as the dates for Bulgarian defaults. Vansittart later estimated that Bulgaria was excused payment of three-quarters of the original reparations; Dockrill and Goold reckoned that “she paid about a third of what was demanded of her in 1919”. Vansittart, The Mist Procession, 235. Dockrill and Goold, Peace without Promise, 101.

[67] Leigh Fermor found that, “On the walls of many of the cafés in this region hung coloured prints of Todor Alexandroff, a Bulgarian Macedonian who had attempted, by propaganda and guerrilla warfare, to hack out a semi-independent state of Macedonia with the capital at Petrich…: a formidable black-bearded man he looks in his picture, scowling under a fur cap, slung with bandoliers and binoculars and grasping a rifle.” Leigh Fermor, The Broken Road, 17.

[68] It was also the hand that had signed the Treaty of Neuilly. The fate of Stamboliĭski, “a great bison with little red furtive eyes” and hands like “large dimpled hams”, drew a warmhearted tribute from Nicolson and a despairing “What swine the Balkans are! My pig farm.” Nigel Nicolson, ed., Vita and Harold: The Letters of Vita Sackville-West and Harold Nicolson (London, 1992), 121-22, Nicolson to Vita Sackville-West, 15 June 1923.

[69] R.J. Crampton, A Short History of Modern Bulgaria (Cambridge, 1987), 99.

[70] Mair, The Protection of Minorities, 185-86. Crampton, Aleksandŭr Stamboliĭski, 129-30.

[71] Leigh Fermor, The Broken Road, 89-92.

[72] On the popular elation that was prompted by Craiova, see Stephane Groueff, Crown of Thorns (Lanham, 1987), 267-68. Romania’s Queen Marie’s heart, buried at her summer palace in Southern Dobrudja (at Balcic) on her death in 1938, was taken to Castle Bran in Transylvania, her other favourite retreat.

[73] “Brute force took the upper hand. Faced with the aggressive German army marching toward the northern border of the country, Boris III had to form an alliance with Germany.” Alexander Fol, Bulgaria: History Retold in Brief (Sofia, 2008), 150.

[74] Plamen S. Tzvetkow, A History of the Balkans: A Regional Overview from a Bulgarian Perspective (New York, 1993), 235. Groueff, Crown of Thorns, 301-2.

[75] Ibid., 302. Marshall Lee Miller, Bulgaria during the Second World War (Stanford, 1975), 123-25.

[76] Tzvetkow, History of the Balkans, 234-5, 241, 251. Pavlowitch, A History of the Balkans, 312-13.

[77] Elemér Illyés, National Minorities in Romania: Change in Transylvania (Boulder, 1982), 82.

[78] Kostanick, ‘The Geopolitics of the Balkans’, in Charles and Barbara Jelavich, eds., The Balkans in Transition: Essays on the Development of Balkan Life and Politics since the Eighteenth Century (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1963), 39.

[79] Leigh Fermor, The Broken Road, 95.