The Battle of Verdun is widely regarded as the greatest battle of the First World War. It lasted 300 days (ten months) between February and December 1916, twice as long as the next longest on the Western Front (the Somme), and it involved sixty-six of the ninety-six divisions of the entire French army and about half of the German soldiers in the west. It was the great test for France when, instead of experiencing a defeat which would have destroyed the morale and fighting spirit of the French, her army stopped the Germans and, from July, was on the front foot, destined not only to save Verdun but also to regain almost all of the land lost in the first half of 1916. The French victory came at great cost, perhaps 375,000 men (including 160,000 deaths), slightly more than the almost 350,000 casualties incurred by the Germans.[1] The destructiveness of the battle, the ghastly conditions and enormous losses suffered in the contest for a few acres of shattered terrain, led later commentators to see only a Pyrrhic victory for France. It was a battle that “had no victors in a war that had no victors” (Horne), “a uniquely awful low point in a conflict that was by no means short of such woeful milestones” (Buckingham).[2] This was not the view of the French in 1916 (nor of the Allied visitors of 1919), who believed that the courage and steadfastness of their army had delivered a victory that saved France. In fact, both those who celebrated victory and those stunned and appalled by its cost were justified in their opinions.

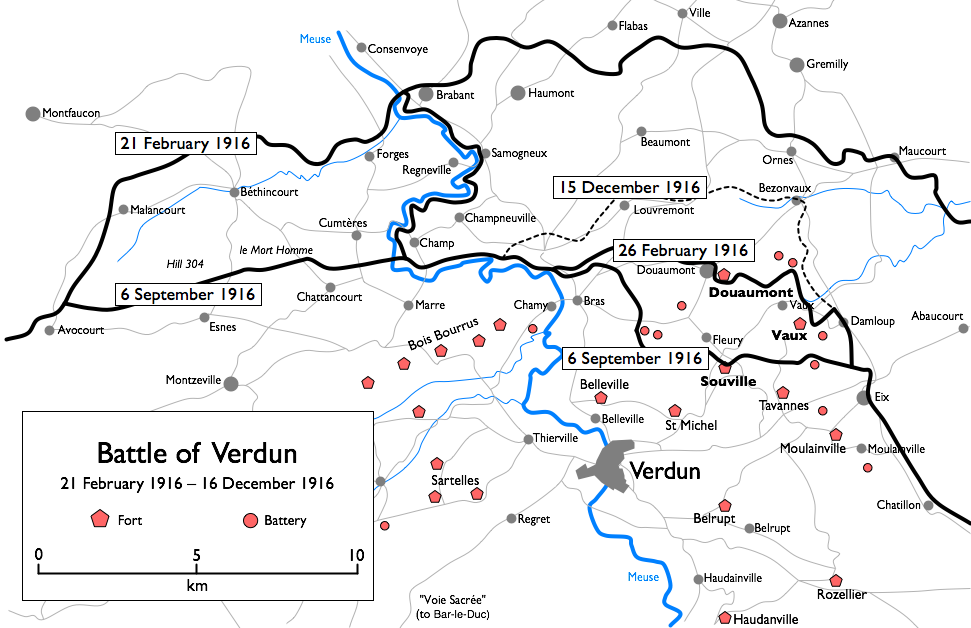

The story of the battle is well known. The Germans had refrained from attacking Verdun’s formidable defences, with its rings of late-nineteenth century forts, in 1914, thus creating a salient (bulge) in the French line that represented a point of weakness. In February 1916, German Fifth Army launched an offensive, Operation GERICHT, against the forts and trenches north of Verdun. General Erich von Falkenhayn’s later (1919)-proclaimed strategy was designed to destroy the French army in a process of Verblutung (bleeding to death), for the French were expected to defend historic Verdun at any cost.[3] Twelve hundred field guns opened fire at dawn on 21 February 1916 and an unprecedented one million shells fell on the French positions that first day – “we fired, fired, fired, without letting up”[4] – with the heaviest fire concentrated on a twelve-kilometres-wide front north and north-east of Verdun.[5] The German infantry, twice as numerous as the French defenders, surged forward at five in the afternoon, probing for the vulnerable spots, and this sequence was repeated the following day. Despite unexpectedly strong resistance, almost the entire French front line, now razed and barely identifiable, was captured by the end of 22 February, the rest fell next day, and the second line was taken by the end of 24 February. French losses soared as reinforcements were quickly devoured by enemy fire.[6]

The story of the battle is well known. The Germans had refrained from attacking Verdun’s formidable defences, with its rings of late-nineteenth century forts, in 1914, thus creating a salient (bulge) in the French line that represented a point of weakness. In February 1916, German Fifth Army launched an offensive, Operation GERICHT, against the forts and trenches north of Verdun. General Erich von Falkenhayn’s later (1919)-proclaimed strategy was designed to destroy the French army in a process of Verblutung (bleeding to death), for the French were expected to defend historic Verdun at any cost.[3] Twelve hundred field guns opened fire at dawn on 21 February 1916 and an unprecedented one million shells fell on the French positions that first day – “we fired, fired, fired, without letting up”[4] – with the heaviest fire concentrated on a twelve-kilometres-wide front north and north-east of Verdun.[5] The German infantry, twice as numerous as the French defenders, surged forward at five in the afternoon, probing for the vulnerable spots, and this sequence was repeated the following day. Despite unexpectedly strong resistance, almost the entire French front line, now razed and barely identifiable, was captured by the end of 22 February, the rest fell next day, and the second line was taken by the end of 24 February. French losses soared as reinforcements were quickly devoured by enemy fire.[6]

Fort Douaumont, on a high plateau north-east of Verdun, had been considered one of the most formidable defensive positions in the world, but recent French military thinking questioned the value of static strongholds (others having fallen alarmingly quickly, as in Belgium in 1914), most of its guns had been redeployed elsewhere (leaving just one fixed gun) and it had only 58 defenders in February 1916. So, “hulking but disarmed and pitifully garrisoned” (Jankowski), “one of the world’s most modern and sophisticated fortifications fell without a fight in the late afternoon of 25 February” (Buckingham).[7] For the next eight months, the Germans defended the fort against frequent French attacks. Margaret Hall went there in January 1919 and was told of how, on one occasion, “a French shell had entered the fort during the German occupation and twelve Germans are buried in the débris”.[8] The deadly explosion inside the fort might have been caused by a French shell, as she thought, but it is possibly attributable to a famous accident that brought the deaths of a much greater number of Germans. On 8 May 1916, Bavarian soldiers in the fort were brewing coffee on upturned cordite cases, using explosive (or alcohol) to boost the fire. This ignited a batch of hand grenades and, in turn, flame-thrower fuel and, finally, after the conflagration flashed through the corridors, a magazine containing artillery shells. The massive explosion killed 679 men, most of the bodies buried and never recovered, and injured 1,800 others.[9] The “shelled-to-pieces condition” (Hall) of the top of the fort was effected during the French reconquest of Douaumont in October 1916, when shells from one of two new 400mm guns, France’s own Big Berthas, shattered the thick concrete roof of the fort and forced its abandonment.[10]

In February 1916, Douaumont gave the Germans control of the most commanding position in the area and the road to Verdun apparently lay open. German planes dropped leaflets telling the French soldiers, “Douaumont has fallen. All will soon be over now. Don’t let yourselves be killed for nothing.”[11] Some French generals, possibly including Joffre, contemplated retreat to more defensible positions in the Argonne, or at least giving up the east bank of the Meuse to reduce the salient, shorten the line and save Verdun. But “military logic was about to become subsumed in the less straightforward matter of national morale, honour and prestige”.[12] Thanks mainly to General de Castelnau (Joffre’s Chief of Staff), the French determined to hold onto both the east bank and Verdun.[13] General Philippe Pétain was put in command of all forces in the Région Fortifée de Verdun on 26 February. Despite a bout of pneumonia, he stiffened the resolve of his subordinates and, proclaiming a new Line of Resistance, began the long struggle to hold every inch of terrain. Pétain’s vigorous leadership, the augmentation of the French artillery and utter exhaustion among the Germans levelled the playing field and German losses (about 25,000 dead, wounded or missing) matched those of the French by the end of February.

On 23 May 1919, James Shotwell approached Verdun from the west and gained an overview of the battlefield before entering the city. The French provided him with a guide, an officer wounded at Verdun, who pointed out the contested hills – Mort Homme, Froide Terre, Douaumont – around Verdun before they entered the town and went to its famous citadel.[14] But Lloyd George and Margaret Hall both approached Verdun along the route that is most evocative of the story of the battle. The road north from Bar-le-Duc became the principal supply route of the French with, at the peak in June 1916, 12,000 trucks moving to and fro around the clock and passing any given spot at a rate of one truck every fourteen seconds.[15] It was Verdun’s lifeline, entering folklore as the Sacred Way (“Voie Sacrée”).[16] Lloyd George, venturing forth in the interval in June 1919 when the peacemakers awaited Germany’s decision on signing the Treaty of Versailles, was accompanied by the journalist who liaised between him and the British press, George Riddell:

[T]he Prime Minister visited Verdun with its ruined town, huge citadel and ring of forts lying within a radius of five miles or thereabouts. He drove along the famous road which saved France and European liberty. Up and down this hilly way every twenty-four hours passed seven thousand motor lorries and other vehicles used for conveying food and ammunition. Almost continuously for six months the road was shelled by the Germans and just as persistently repaired by the French. The Frenchman who drove the Prime Minister remarked, “There! That is my dug-out! I used to travel this road twice a day. On two occasions my lorry was hit, but I escaped. Was I wounded? Yes! (shrugging his shoulders) but it is nothing![17]

In fact, the Sacred Way was out of range for most of the German guns, which was why it served the French well, and only the section close to Verdun was regularly shelled.

| The citadel

All of these visitors spent some time in the great citadel in the centre of Verdun. This was not Pétain’s headquarters, which lay south of town at Souilly, but, able to accommodate up to 20,000 men, it was a major way-station for troops – “a real underground town”, its “warren of passages and chambers … was employed as a shelter, barracks, HQ, cookhouse and supply depot all rolled into one” and it “acted as a staging-post for units moving up to the line”[18] – and a target of constant German bombardment in 1916. The well-connected Shotwell enjoyed French hospitality in the citadel before (and after) going out to the nearby forts and was given a taste of the underground life of the occupants: As the Germans had shelled the town, the only places left intact for visitors were the tunnels or galleries which the French had built through the solid rock of the citadel. They have built seven and a half kilometers of these galleries from fifteen to twenty feet wide and about as high… [T]he commandant took us through the tunnels and galleries of the citadel. He is very proud of these, having dug two kilometers himself. There was a chapel with some beautiful statuary and carved woodwork rescued from the cathedral; but the hall which he had fitted up for an amateur theatre was the most interesting place. Its walls were hung with banners and it was there that the ceremony took place in which the city of Verdun itself was accorded military honours [by President Poincaré and other French and Allied leaders on 13 September 1916]… There was also a huge bakery with apparatus for mixing bread for thousands of men and even a mill in one of the galleries, and little railway tracks ran through them all…[19] Lloyd George was welcomed by a French general and honoured with a tour of the citadel, a good lunch and fulsome tributes from his hosts. Riddell described an occasion of high emotion, as the French recalled the British leader’s previous visit and his steadfastness as their ally, and Lloyd George praised those who “bore the flag of liberty in the darkest hour”: The Prime Minister lunched in the famous citadel, the home of two thousand brave Frenchmen. With its long radiating tunnels it reminds one of an underground railway junction. As the Prime Minister walked into the tunnel in which lunch was served, the band played “God Save the King” and the “Marseillaise”. Flowers decked the table and the lunch was excellent, but it was a quiet, thoughtful little party, and Colonel Sarot, the Commandant, and the Prime Minister made frequent references to the latter’s previous visit when the battle was raging in 1916. Taking Mr. Lloyd George to another tunnel, Colonel Sarot said, “Here you made your speech. Do you remember that night?”[20] After lunch General Valentine made a graceful little speech in which he referred to the comradeship between France and Great Britain and to the services rendered to France by Mr. Lloyd George. The Prime Minister made a brief but eloquent reply, and then once more we were out again in the sunshine and driving through miles of shattered buildings, which everyone ought to see to appreciate how France has suffered. At Chalons the Prime Minister visited General Duport, the inventor of the famous “seventy-five” [gun], who reminded Mr. Lloyd George of the Conferences they had attended during the war. Then back to Paris, full of admiration for the tough, virile people who, as Mr. Lloyd George said in his speech, “bore the flag of liberty in the darkest hour”.[21] It is interesting that Lloyd George still thought in such terms at a time, June 1919, when he was extremely unhappy with the French line, its excessive harshness, on the treaty with Germany. Lloyd George clearly understood the French point of view and could be tugged back towards it by events, including this reminder of the magnificent courage and accomplishments of the French army. Margaret Hall showed an appreciation of the soldiers’ miserable experience in the citadel when she described the officer in charge of the Foyer de Soldat (soldiers’ hostel) as “one of the most pathetic I’d seen in France. He looked so pale and sick, and by his color you could tell that sunshine was what he needed, and not the artificial light and artificial air of subterranean life. His “cafard” was beyond cure. He had lost every friend and companion he had – all killed, he told us, and life for him was too dismal to be endured, and it didn’t look as if he’d have to endure it much longer.[22] |

Through March and April 1916, there was deadlock on the east (right) bank of the Meuse and the Germans there were shelled unceasingly by French artillery massed on the opposite bank. To stop this, Falkenhayn was persuaded by his subordinates (Fifth Army commander Crown Prince Wilhelm and Chief of Staff Schmidt von Knobelsdorf), to begin an offensive on the west bank. The Germans launched a succession of attacks on the Mort Homme (Dead Man’s Hill), which loomed above the west bank artillery emplacements. Some of the fighting here matched the intensity (and losses) of the great battle on the east bank in February. It was the failure of one such attack, that of 9 April (when the Germans attacked simultaneously on both sides of the Meuse), that prompted Pétain’s most famous words: his order of the day of 10 April 1916 praised the magnificent defence of the Mort Homme and finished with saying, Courage, on les aura! (Courage, we’ll have them yet!), invoking Joan of Arc’s rallying cry, “nous les aurons!”, at Orléans. Hill 304, three kilometres to the west, from where machine-guns strafed the Germans as they assailed the Mort Homme, had its height reduced by several metres by a 500-gun bombardment lasting 36 hours. It finally fell early in May and the Mort Homme followed at the end of the month. Margaret Hall, Charles Seymour and James Shotwell all visited the Mort Homme: Hall had the rather fanciful notion that the Germans planned to tunnel through it to Verdun and Shotwell spoke in general terms about the hilly, ruined landscape (“the field of shell craters”) all around.[23]

On 1 May, frustrated with Pétain’s defensive strategy, Joffre replaced him as head of Second Army with Robert Nivelle, a general who believed in l’attaque à outrance (and in himself).[24] This quickly yielded another setback, when Nivelle’s battering ram, Charles Mangin (“the butcher” or “le mangeur des hommes” – the eater of men), tried and failed (expensively) to retake Douaumont on 22-24 May 1919.[25] Five kilometres away, Fort Vaux, the smallest of all of the forts around Verdun, fell to the Germans on 7 June after a week-long battle which culminated in fierce hand-to-hand combat in the passages inside the fort. A visit to Vaux was on Lloyd George’s itinerary a year later:

The Prime Minister visited the fort which was temporarily [June to November 1916] taken by the Germans – a dark gloomy place with long underground tunnels. Here by the electric light the General displayed the dints in the stone made during the desperate fighting which took place in this underground cavern. The tiny little chapel, some twenty feet long by six feet broad, with its domed roof, was specially [sic] remarkable. The walls are scored and dented by the grenades and bombs used in the hand to hand fighting.[26]

Margaret Hall and Shotwell saw the same evidence, including holes in the walls made by grenades and bullets, of the struggle.[27] After the Germans broke into Vaux, on 2 June, the conflict was unimaginably ferocious: it was “the scene of hellish underground fighting of a scale and intensity that occurred nowhere else on the Western Front” with men “struggling and clawing at one another hand-to-hand in pitch blackness…” (Buckingham). In corridors barely three feet wide, German soldiers rushed the French defences (commonly machine-gun posts behind sandbags) and faced determined defenders often reduced to fighting with spades and bayonets, only to find, once they prevailed there, that another such position had been set up further along the tunnel. In five days, the Germans managed to advance only 65 metres and one day they made five metres! They introduced toxic gases (and grenades) through breaches in the roof of the fort and used flamethrowers to pump fire into the fort and spread fumes and “thick clouds of choking black smoke”.[28] After several days, the defenders began to run out of water, the last of the supply was contaminated by putrefying corpses, and the men were reduced to licking condensation from the walls or drinking their own urine. A feeble, belated attempt to relieve the fort on 6 June was beaten off and the French surrendered the following morning. The attack on Vaux cost the Germans almost 3,000 men, while the French lost not much more than a hundred. On 8 June, the Zouaves and Morocans sent to retake Vaux suffered much greater losses in possibly the most “futile and bloody” action of the entire battle of Verdun.[29]

All of the visitors in 1919, though experienced students of the battlefields by the time they went to Verdun, were shocked by the scenes of devastation all around. “As far as the eye can reach in every direction,” wrote Riddell, Lloyd George’s companion, “one saw every yard of ground churned up by innumerable shells. Devastation and desolation everywhere,” even if, because it was mid-June, “the poppies painted the landscape a vivid red, and many of the poor scarred tree stumps were putting out little green shoots.”[30] According to Shotwell,

No description of the battlefield of Verdun is possible. I cannot conceive of anything more awful than the great bare hills around Douaumont. Ypres is of another quality. Both of them symbolize the utmost that has ever been suffered and endured by men from the beginning of the world.

His guide told him that most of the bodies of those who fell “have been literally blown into the soil. Even along the little footpath we took to Douaumont, we passed shell craters with the bones of skeletons showing openly”.[31]

For Charles Seymour, too, Verdun was now a monument to man’s destructiveness: “the whole landscape is nothing but a series of shell-holes… always the same desolation intensified by the thousands of crosses which stick up from the mud… It is without question the most lugubrious sight I ever saw in my life… For large areas even the weeds are unable to grow, a whole side of the hill being absolutely white with the subsoil turned up by the shellfire.[32] Hall passed through similar scenes of devastation – “through those barren, desolate, gray hills, all shot to pieces, without a tree or a living thing anywhere for miles and miles; trenches near by and in the distance, going round and over the hills, barbed wire, shell holes” – and was deeply conscious at one point of being “alone with the dead”, their bodies “left to the end of time – each with a little wooden cross decorated with the French cockade, to show that it was “for France” that they were there.”[33]

*************

The fall of the Mort Homme and of Fort Vaux augured well for a final German push on Verdun. June brought an intense struggle to capture the Ouvrage (bunker) de Thiaumont, a commanding position seen as the key to taking Fort Souville and, in turn, Verdun. On 11 June, No. 3 Company of the 137th Infantry Regiment, from the Vendée, came under shellfire in their trench just north of Thiaumont. After two days and a night of heavy bombardment, the 164-strong company was no more: the soldiers had been buried alive, still holding their rifles, when the trench collapsed. The bodies were discovered after the regiment’s Colonel Collet, posted again to Verdun in January 1919, investigated the fate of the company; his account of how a row of bayonets protruded from the soil and, beneath the surface, the men stood upright holding their rifles gave birth to the legend of the Tranchée des Baïonnettes. In May 1919, Margaret Hall visited the “bayonet trench” and noticed that, on a monument, Pétain’s “On les aura” had been used to celebrate the unbreakable will of the French.[34]

Other men, disillusioned with an endless struggle that had yielded not a single French victory, broke and ran from (or refused orders to return to) their trenches, a forestaste of the “mutiny” of 1917. Joffre’s focus on the Somme, soon to be the site of the great, war-winning (it was hoped) Anglo-French offensive, denied Second Army reinforcements and new guns at Verdun. On 22 June, the German bombardment featured 116,000 phosgene gas shells, a deadly addition to military technology which caused panic among the enemy, and the German infantry went forward just after dawn on 23 June and took a number of key positions, including the Ouvrage de Thiaumont and the village of Fleury. But most of the French units managed to hold on, rallied, perhaps, by Nivelle’s famous order, “Ils ne passeront pas!” Russia’s 4 June offensive in the east meant that three German divisions were switched to Galicia to prevent a total Austrian collapse, a move that may have fatally weakened the attack on Fort Souville. There were not enough phosgene gas shells for a repeat performance, and a lack of drinking water proved debilitating. The German attack could not be sustained. According to Horne, “basically, the foundering of the German attack all boiled down to the shortage of manpower” and, by the evening of 23 June, Schmidt von Knobelsdorf, Fifth Army’s Chief of Staff, “knew that his supreme bid to take Verdun had failed”: his army “was exhausted, French resistance was stiffening, and soon the inevitable counter-attacks could be expected”. The advance had created a narrow salient which French counter-attacks hacked into from both sides.[35] The gains of 23 June were the furthest point that the Germans managed and, though they retained Thiaumont and Fleury, they were incapable of taking Fort Souville.

The bombardment at the Somme began on 24 June, the British and French infantry went over on 1 July, and that battle became everyone’s primary focus for the rest of the year. Neither side could spare the resources for a decisive initiative at Verdun. Another German advance on Fort Souville, on 11-12 July, rapidly petered out and was turned back by the French, who had been issued with more effective gas-masks. This has been called “the effective end of Operation GERICHT” after “139 days of constant bloodletting”; Fifth Army was now ordered to remain “strictly on the defensive”.[36] Much of the fighting between mid-July and mid-August involved French attempts to regain Fleury (which they finally managed to do in October), during which the village changed hands sixteen times and was entirely destroyed.[37] It was one of Seymour’s destinations in May 1919: “At one point we stopped and on consulting our map found that we ought to be at a village called Fleury; we looked around and found as a matter of fact a few bricks and stones, and realized that we were on the site of the village, which had completely disappeared.”[38]

In August 1916, for the first time, German casualties exceeded those of the French. Falkenhayn and Knobelsdorf were transferred to other fronts (the Romanian and Russian, respectively) at the end of August and their successors, concluding that Verdun “exhausted our forces like an open wound…[T]he enterprise had become hopeless” (Hindenburg) and “a nightmare… Our losses were too heavy…” (Ludendorff), formally terminated GERICHT on 2 September 1916.[39] It was during the relative lull of September 1916 that Lloyd George, then the War Minister, had gone to Verdun for the first time. He dined in the citadel on 7 September and declared in a short speech that,

The name of Verdun alone will be enough to arouse imperishable memories throughout the centuries to come… The memory of the victorious resistance of Verdun will be immortal because Verdun saved not only France, but the whole of the great cause which is common to ourselves and humanity. The evil-working force of the enemy has broken itself against the heights around this citadel as an angry sea breaks upon a granite rock. These heights have conquered the storm which threatened the world. I am deeply moved when I tread this sacred soil…[40]

This was the occasion that Lloyd George relived in the citadel in June 1919.

The final rounds of the great battle saw the French reconquest of Douaumont (and the Ouvrage de Thiaumont and Fleury) on 24 October, their infantry advancing behind the “creeping barrage” laid down by the artillery, the Germans gave up Vaux on 1-2 November, and the French pushed back “the utterly demoralized enemy force which, by this stage, could offer hardly any resistance” (Mason) all along the line during the last weeks of the year.[41] The late-1916 gains of the French, their “most brilliant victory since the Marne” (Horne), and the onesidedness of the contest were reminiscent of the German success of February 1916, at the beginning of the battle, although Mort Homme and Hill 304, on the west bank, were not retaken until August 1917 (and some territory lost in February 1916 was not regained until 8 November 1918, by the Americans).[42] The Germans had failed to take Verdun and their losses were close enough to those of France to obviate any idea of success in terms of attrition (“bleeding white”) of the French army. In fact, as with all of the great Western Front battles between 1916 and 1918, it was the Germans who lost most in proportion to their relatively limited resources – “This battle exhausted our forces like a wound that will not heal” (Hindenburg) – and the failure greatly damaged their morale: Verdun “ground up the hearts of the soldiers as much as their bodies” (Crown Prince Wilhelm).[43]

Though staggered by the destructiveness of the titanic struggle, those who visited Verdun in 1919 did not regard the battle as the Pyrrhic victory that historians have described. It was the battle in which the “poilus” of France saved their country from defeat and prevailed by virtue of indomitable spirit, selflessness and courage, their “invincible resistance”. This was the sentiment expressed by Lloyd George when he spoke in the citadel in June 1919. Shotwell was given a glimpse of the attitude in France when he returned from his May 1919 visit to Verdun:

When I came back to Paris I gave my clothes to the chambermaid to be cleaned, and remarked that the white mud was hard to get out, that it was the dust of Verdun. She took the clothes reverently and said with a tone that I shall never forget, “That is very precious dust, sir.”[44]

It was Verdun that Margaret Hall recalled when she heard her countrymen accusing the French of leaving it to the Americans to take the main brunt of the conflict in the last months of the war: “I am convinced that every American soldier who stands on the top of Fort Douaumont and … looks at the desolation of that shell-torn country, knows that “The Iron Wall of France”, the poilus, deserve, instead of our criticism, our utmost admiration.”[45]

[1] The statistics vary greatly. These are from Paul Jankowski, Verdun: The Longest Battle of the Great War (Oxford, 2013), 116-120.

[2] Alistair Horne, The Price of Glory: Verdun 1916 (London, 1962), 331. William F. Buckingham, Verdun 1916: The Deadliest Battle of the First World War (Stroud, 2016), 193-94. Buckingham was expressing popular perception here.

[3] On the difficulty of reading Falkenhayn’s intention – “Was Ausblutung a possibility or a plan?” – see Jankowski, Verdun, 27-46. See also David Mason, Verdun (Moreton-in-Marsh, 2000), 16-20, 186-88.

[4] A German gunner quoted in Jankowski, Verdun, 10.

[5] All of the histories of Verdun describe this bombardment, but Ian Ousby’s account of its awesome impact is especially compelling, and distressing. Ian Ousby, The Road to Verdun: World War I’s most momentous battle and the folly of nationalism (New York, 2003), 80-87.

[6] Sometimes literally, for this battle saw the debut of the flamethrower.

[7] Jankowski, Verdun, 20. Buckingham, Verdun 1916, 127-29. It fell “without a shot being fired”. Greenhalgh, The French Army and the First World War, 136.

[8] Hall’s memoir, 11 January 1919, in Higonnet, Letters and Photographs from the Battle Country, 114.

[9] Horne, The Price of Glory, 219-20. Buckingham, Verdun 1916, 178-79.

[10] Horne, The Price of Glory, 311-12. Buckingham, Verdun 1916, 243-44.

[11] Horne, The Price of Glory, 122.

[12] Buckingham, Verdun 1916, 135.

[13] “Honor, pride and morale … left the French no choice but to stand where they now stood.” Ousby, The Road to Verdun, 121. Joffre’s position was unclear; the most important advocate of full-scale retreat was General de Langle de Cary, the Commander of Army Group Centre.

[14] Shotwell, At the Paris Peace Conference, 328-29, Diary, 23 May 1919.

[15] Horne, The Price of Glory, 148.

[16] Ousby also called it the Via Dolorosa, an Assent to (or Descent from) the Cross, and a Descent into the Inferno. Ousby, The Road to Verdun, 9, 12, 24, 318-19.

[17] Riddell Diaries, Add MS 62964, f22, Account of Trip to Verdun, 18-19 June 1919. Also in Lord Riddell, Intimate Diary of the Peace Conference and After, 1919-1923 (London, 1933), 95.

[18] Buckingham, Verdun 1916, 176-77.

[19] Shotwell, At the Paris Peace Conference, 329, 334, Diary, 23 May 1919.

[20] Lloyd George’s visit to Verdun in September 1916 is noticed below.

[21] Riddell Diaries, Add MS 62964, ff23-4, Account of Trip to Verdun, 18-19 June 1919. Also in Lord Riddell, Intimate Diary of the Peace Conference and After, 1919-1923 (London, 1933), 96-7.

[22] Hall’s memoir, 11 January 1919, in Higonnet, Letters and Photographs from the Battle Country, 109-10. The word “cafard” literally meant cockroach, but it was used by the poilus to mean depression or melancholy. Ousby, The Road to Verdun, 20.

[23] Hall’s memoir, [April] 1919, in Higonnet, Letters and Photographs from the Battle Country, 142. Shotwell, At the Paris Peace Conference, 334-35, Diary, 24 May 1919. Letters from Charles Seymour, 238, Seymour to Mr and Mrs Thomas Watkins, 21 May 1919.

[24] Pétain replaced Langle de Cary as Commander of Army Group Centre and was relieved of specific and day-to-day responsibility for Verdun; his new HQ was at Bar-le-Duc.

[25] The effort caused almost 5,500 casualties, including nearly 900 dead, out of 12,000 men. Ousby points out that “it was French troops, as much as German, of whom Mangin was said to be a mangeur.” Ousby, The Road to Verdun, 279, 320.

[26] Riddell Diaries, Add MS 62964, f23, Account of Trip to Verdun, 18-19 June 1919.

[27] Hall’s memoir, [April] 1919, in Higonnet, Letters and Photographs from the Battle Country, 142. Shotwell, At the Paris Peace Conference, 332, Diary, 23 May 1919.

[28] Buckingham, Verdun 1916, 9, 199-201. Mason, Verdun, 154-55. The flame-throwers “”would smoke Vaux’s heroic garrison out like rats”. Horne, The Price of Glory, 258.

[29] Horne, The Price of Glory, 266. See also Buckingham, Verdun 1916, 209-12, “another bloody and fruitless debacle”.

[30] Riddell Diaries, Add MS 62964, f22, Account of Trip to Verdun, 18-19 June 1919.

[31] Shotwell, At the Paris Peace Conference, 329-31, Diary, 23 May 1919.

[32] Letters from Charles Seymour, 237-38, Seymour to Mr and Mrs Thomas Watkins, 21 May 1919.

[33] Hall’s memoir, 11 January 1919, [April] 1919, in Higonnet, Letters and Photographs from the Battle Country, 111-13, 141. This is a very small extract of Hall’s full and vivid description of her visits to Verdun.

[34] Hall’s memoir, 26 May 1919, in Higonnet, Letters and Photographs from the Battle Country, 153. Horne and Ousby reckoned they had been found dead and were buried by the advancing Germans, who used the rifles to mark the graves. Horne, The Price of Glory, 268-69. Ousby, The Road to Verdun, 342-43. Jankowski described the “chimerical legend”, the “apocryphal” site where one could see “the everlasting vestiges of the French will to resist”. Jankowski, Verdun, 86.

[35] Horne, The Price of Glory, 292. See also Buckingham, Verdun 1916, 226-27. Ousby, The Road to Verdun, 294-97.

[36] Buckingham, Verdun 1916, 235. Mason, Verdun, 168.

[37] Buckingham, Verdun 1916, 239. Ousby has it steadily destroyed from February. Ousby, The Road to Verdun, 339-40.

[38] Letters from Charles Seymour, 237-38, Seymour to Mr and Mrs Thomas Watkins, 21 May 1919. Fleury was one of nine villages that were never rebuilt, it is officially known as a “village détruit” and a “village that died for France”; Wikipedia describes it as “unoccupied (official population: 0)”.

[39] Horne, The Price of Glory, 304.

[40] John Grigg, Lloyd George: From Peace to War, 1912-1916 (London, 1985), 380-81. Although even his Anglophone listeners struggled with Lloyd George’s Welsh accent and “rapt style of oratory”, the speech was well received and one officer said, “We had no need to understand what he said to guess that his theme was sacrifice and glory.” Ousby, The Road to Verdun, 330.

[41] Mason, Verdun, 179. On the sorry state of the Germans, see also Buckingham, Verdun 1916, 249. Horne, The Price of Glory, 310-11.

[42] Ibid., 317.

[43] Mason, Verdun, 188. Mason considered the battle a “massive calamity” for Germany; “the reality [was] that the Germans had sustained horrific losses in their failed quest for Verdun.” Ibid., 190.

[44] Shotwell, At the Paris Peace Conference, 342, Diary, 25 May 1919.

[45] Hall’s memoir, [April] 1919, in Higonnet, Letters and Photographs from the Battle Country, 147.